Who the hell is the Food Professor?

Sylvain Charlebois is the media's favourite food expert. He's also taken $60K from the Weston Foundation.

Sylvain Charlebois wants you to know high food prices are the fault of everyone but the big grocers.

It’s no exaggeration to say Charlebois is the Canadian media’s favourite food expert, so much so that he’s adopted the moniker of the “Food Professor”.

In 2022 alone, the Dalhousie University academic’s name appeared in 156 stories on the CTV News website, 87 on the Toronto Star’s, 55 on the CBC’s, 55 on the Globe and Mail’s and 20 on Global News.

These numbers include Canadian Press wire stories and newsletters that refer back to previously-published stories, as well as op-eds written by the man himself, but they nonetheless give you a good sense of his prominence.

With the notable exception of Jordan Peterson, I can’t think of a single Canadian academic with as large a media footprint. And Charlebois can always be relied on to provide PR for Canada’s largest grocers while presenting himself as a brave truth teller willing to buck the conventional wisdom that corporate profits are out of control, even when his academic research suggests otherwise.

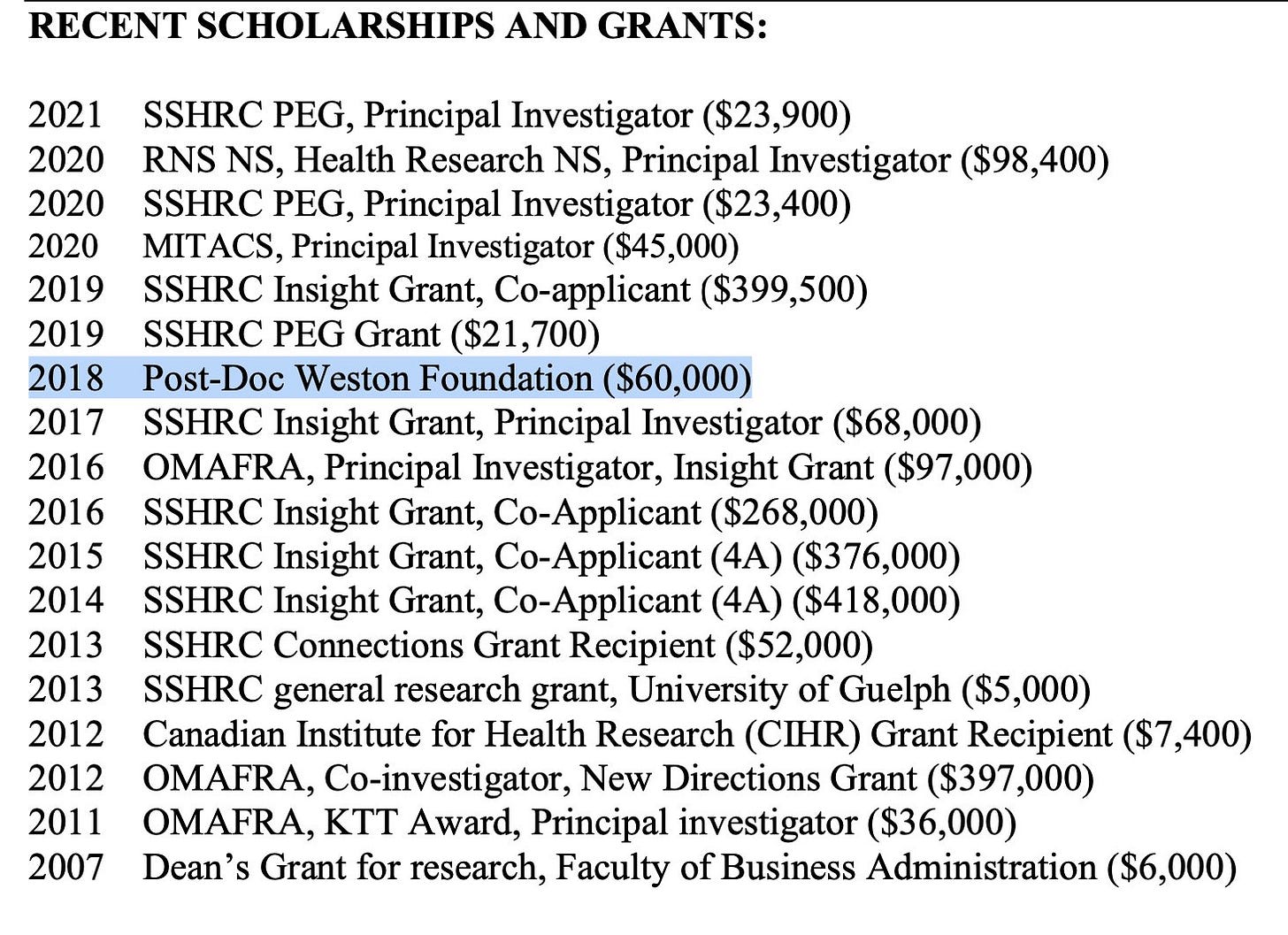

Not one of these articles disclose the fact that in 2018 he received a $60,000 grant from the Weston Foundation, according to his own CV, which has for some odd reason been scrubbed from his faculty page on Dalhousie’s website. But thankfully, we have the Wayback Machine.

The Weston family owns Loblaws — Canada’s largest grocery store chain — in addition to Shoppers Drug Mart, Real Canadian Superstore, No Frills and T&T Supermarkets. Charlebois frequently defends the company, and the industry writ large, against allegations that they’re profiting from high food prices.

When I asked on Twitter why the Food Professor never has to disclose this apparent conflict of interest, Charlebois, who paid for a blue check, got a bit defensive.

Fair enough, nobody likes having their credibility questioned. But he responded as if nobody has ever had the temerity to ask about it, which would itself be problematic.

“I’ve never been paid by the Weston Foundation, personally [emphasis mine],” he replied. However, he did confess to receiving a $60K grant from the Westons “several years ago so I can pay students.”

This response is interesting because I never accused him of pocketing the money. But if his students’ research is funded by a corporate endowment, which unfortunately is common practice in academia, it might leave the impression that their supervisor’s oversight is skewed in a certain direction.

Most notably, he falsely claimed the grant ended in 2017, when in fact his CV says it began the following year.

He said if I have a problem with that, I should call the school’s legal department and “take a number.” This is fascinating for two reasons — firstly, I never accused him of doing anything illegal; secondly, he implies that he often is accused of doing so.

Regardless, my issue is with the Canadian media, not Dalhousie University.

In a Jan. 9 Globe and Mail op-ed headlined, “$37 chicken wasn’t Galen Weston’s fault, but Loblaw1 needs to repent nonetheless,” Charlebois responds to the backlash over Loblaws charging an exorbitant price for five boneless chicken breasts.

This fact was brought to light in a viral tweet from Toronto-based CTV News journalist Siobhan Morris, which Charlebois argues provoked “instant, and mostly vicious” attacks on Loblaw CEO Galen Weston.

“On the surface,” Charlebois wrote, “the collective uproar against Loblaw lacked any rational thinking. The chicken breasts in the picture were skinless, boneless, and free from hormones and antibiotics, which would make them premium products.”

But even then, he argues this was largely the result of an avian flu outbreak, which has put pressure on the industry, including egg producers.

These talking points are almost verbatim what Loblaw is telling the media.

The company told CTV that these chicken breasts are “premium” products, as indicated by the “PC FF” on the label.

“In addition to general inflationary pressures, as I’m sure you are aware, the price of poultry has increased over the last year or so across North America for a number of reasons including demand and disease,” the company continued in its statement.

Yet, as reported by Alex Cosh at The Maple, this is quite different from what the company is telling shareholders.

In its most recent quarterly report, the company boasted of a 30.8% gross profit increase, which it attributed to a “positive financial and operating performance as it continued to execute on retail excellence in its core businesses while advancing its growth and efficiencies initiatives.”

The report also boasts that Canada has the lowest food inflation rate in the G7 — another talking point repeated verbatim in Charlebois’s op-ed — as if Canadians struggling to afford groceries ought to care that other countries have it worse.

According to a report co-authored by Charlebois, in the first half of 2022 Loblaw beat its previous highest gross profit margin of the past five years by $180 million. That’s about $1 million a day.

Naturally, this was through no fault of their own, but because “the pressure for Canadian grocers to deliver quality, safe food to Canadians is immense.”

In a CBC piece about the report, Charlebois said it’s unclear whether these increased profits came from groceries, because “companies are massive and quite diversified from a retail perspective.”

“It's … possible grocers have increased their margins on food. We just don't know," he told the CBC.

Hold on to that thought, because it’s going to come in handy shortly.

Back to the Globe piece, Charlebois never goes beyond his admitted surface-level analysis, in characteristic fashion accusing consumers of “actively looking for a scapegoat” for food prices.

He continues to scold idiot consumers for not understanding the nuances of exorbitant food prices:

Most consumers barely appreciate how farming, logistics or even food processing work, but most of us often go to a grocery store. It’s a familiar environment. However, grocery stores are also portals to a very complex food system we can barely see and understand, so promptly blaming grocers for overpriced products is instinctive.

This is all easy for Charlebois to say. According to Nova Scotia’s sunshine list for 2021-22, he made a cool $221,562 — more than double what Dalhousie faculty on the lower end of the pay scale make. Suffice it to say, he has no difficulty affording groceries, whatever their price.

Charlebois also blames supply chain issues for the price increases he insists aren’t so bad. I have no doubt the supply chain plays a role in increasing food costs, but when you look at Loblaw’s increased profits, it makes one wonder why their bottom line wasn’t impacted.

When he does finally get around to criticizing Weston and Loblaw — to which he dedicates two paragraphs out of 14 — it’s on purely optical grounds.

Weston was a no-show at an inquiry into food prices at the parliamentary standing committee on agriculture and agri-food, sending instead his “financial goons” to testify, Charlebois notes.

“The CEOs should have had the decency to show up and oblige our House of Commons, which represents the Canadian people,” he wrote.

He ends the piece by advising grocers to demonstrate “more public empathy,” and telling “hyper-sensitive” consumers to “stay calm and read labels.”

If you’re going to write an explicit defence of a company you’ve taken money from, the least you could do is disclose that fact. And if you don’t, the least your editors could do is make you disclose it.

The same day as his Globe piece, Charlebois published an op-ed headlined, “We all pay for grocery theft,” which was published across the Postmedia chain. While his Globe piece suggests grocery store CEOs are the last people to blame for high food prices, the Postmedia piece suggests people stealing food are a major culprit.

“Grocery theft has always been a major problem, but with food inflation as it is, shopkeepers now fear the wrongdoers more than before,” he wrote in the lead. Note the emphasis on “shopkeepers,” rather than people who are engaging in petty theft because food prices are spinning out of control.

In the following paragraph, our Food Professor uses two examples to buttress his argument — “some Ontarians” stealing $4,000 worth of meat in Trois-Rivieres and three people in Sherbrooke stealing $2,000 worth of groceries.

Given the scale of their heist, he says these people were likely planning to sell food on a “resale market, likely in the food service industry.”

Now you may ask yourself, why would there be a black market for food in a country of such abundance as ours? If you did, then congratulations, you’ve engaged in more critical thought than the Food Professor.

Four paragraphs later, Charlebois acknowledges that the average food retailer in Canada has an average of $2,000 to $5,000 worth of food stolen per week, showing how extreme an outlier the two examples he cites are.

“With the relatively narrow profit margins in grocery, this amount is huge. To cover losses, grocers need to raise prices, so in the end, we all pay for grocery theft,” he wrote, praising the “discreet tactic” of having plain clothes security officers patrolling stores as “very effective.”

But by Charlebois’s own admission noted earlier, we don’t know how much of grocery companies’ profit margins come from food.

He cautions that ”your favourite grocers won’t have a choice” but to step up surveillance of their stores, as if reducing prices and cutting into the companies’ growing profit margins weren’t an option.

When Charlebois discusses the perils of self-checkout, it has absolutely nothing to do with putting grocery store workers out of a job. His sole concern is that it makes it easier to steal.

The question of why people would steal from grocery stores simply doesn’t cross his mind. If it did, he would have a harder time waving away concerns about the impact of inflation on most people’s day-to-day lives.

For Charlebois, these issues are always presented from the retailer’s point of view, whom we are told have no choice but to raise prices due to forces beyond their control. Remember, times are tough for everyone. Don’t be selfish.

If you, a consumer, don’t like it, Brian Lilley has free advice for you to make smarter shopping decisions.

Edited by Stephen Magusiak

Loblaw is the name of the Westons’ company, Loblaws is the store’s name.

I was discussing this guy’s comments about “theft” with someone who has worked for 20+ years in the grocery industry, and a couple of interesting points about the “theft” numbers.

1). When inventory is done (usually quarterly), any “unaccounted for product” goes into an accounting bucket labelled “variance”. Variance is a bit bucket for product that is missing without explanation.

2). Included in that bucket are product that arrives damaged that cannot be refunded for credit, product that ages off the shelf on expiry dates, stuff that gets dropped on the floor, etc. In theory, these companies have procedures for “scanning out” anything that is being disposed of, but not all staff know about those procedures or actually execute them. There are perverse reasons for this, including the way that “shrink” (loss due to aging out product) is measured, and often weaponized against floor staff.

3). When product is accounted for in the “variance” bucket, it is based on full retail ticket price, not the cost at the receiving dock, with no tracking of whether it was on sale, or marked down.

4). Damaged product in theory can be returned for credit, but the processes are often so onerous that the people responsible for them find it easier to let the product disappear into “variance” and just throw it away.

The bucket of things in the “variance” is huge, and the greater proportion of them often being matters associated with internal operations losses. Yet they take this number and represent it in part or whole as “theft”. (And the numbers around “in part” are often arbitrary)

When you are running the operation primarily on casual staff that work way less than 40 hours a week for you, it’s hardly surprising that people take shortcuts on procedures that they deem “too much effort”. Most of those casual workers are holding down 2 or 3 jobs to make “ends meet”. The number of full time staff who understand the operations is very limited.

The employment picture not only engenders a “DGAF” attitude among many workers, but it means that fewer staff have the necessary skills with tasks like ordering, and centralized or automated ordering schemes often mean huge amounts of product shoved at stores where the product won’t actually sell for one reason or another.

So, when you see articles claiming that “theft” is a huge problem, one might be inclined to ask exactly what they are including as “theft” - because there can be a lot of not-really-stolen product in that pile.

Retail theft has always been a problem, but let’s not kid ourselves when executives start braying about it when the level of precision in the data is so low, and frankly the industry has decided that paying people a living wage is no longer necessary. Underpaid workers aren’t going to invest the effort to develop the skills needed, and there are limits to what automation can achieve here.

There is a question of what effect recent supply chain disruptions have had on food availability. I don't care about Weston's bottom line but I do care about the real impacts for those of us needing to feed ourselves. It would be fantastic if a well funded researcher like Charlebois could do a deep dive into systemic change in what shows up on the shelves, but of course he won't.