U of A security called pro-Palestine encampment "extremely peaceful" a day before police tore it down

The Orchard obtained more than 200 pages of heavily redacted internal communications about the protest camp, which was dismantled in the early hours of May 11, through FOIP.

Tl;dr

Internal emails obtained through FOIP show that University of Alberta campus security repeatedly referred to a pro-Palestine encampment on campus as “peaceful” the day before administration invited police to dismantle it by force.

Hours after the Orchard reached out to the University of Alberta for comment, the university released the results of a third-party investigation from Justice Adele Kent into how the university handled the encampment that was submitted on Oct. 30.

Kent’s conclusion echoed university president Bill Flanagan’s claim that the encampment posed a risk to campus security due to the presence of wooden pallets, which they speculated were intended to build a barricade.

An email from campus security obtained in the FOIP said that they asked the encampment to remove the pallets, citing a fire hazard. Three encampment members who spoke to the Orchard confirmed that they complied with this request.

The documents include an email from a member of the public accusing the encampment of antisemitism, claiming as evidence a sign that had the word Jews on it. A Jewish faculty member who was at the encampment said this was a reference to a banner that Jewish supporters brought to express their support.

In the early hours of May 11, 2024, Edmonton police officers dressed in riot gear forcefully dismantled a pro-Palestinian encampment at the University of Alberta just two days after students, faculty and broader community members pitched tents in the Quad to protest what a growing chorus of leading experts in Holocaust and genocide studies have characterized as genocide.

In a community update issued after the encampment was torn down, UAlberta president Bill Flanagan defended the heavy-handed response, arguing the protest posed a threat to campus “safety.”

But documents obtained through a FOIP request call Flanagan’s assessment into question.

In internal communications, campus security repeatedly referred to the encampment, which also included MacEwan University students from the other side of the North Saskatchewan River, as “peaceful”—and in one instance, “extremely peaceful”—throughout the short duration of its existence.

Security officials re-assured encampment organizers, even after trespass notices were issued, that they were at no risk of eviction if the status quo in the Quad was maintained.

The heavily redacted documents provide little indication of why the university leadership changed its mind and decided to call in the cops to put an end to the encampment.

“I don't think it's a wild stretch to think there are outside forces at play here,” Nour Salhi, a MacEwan journalism student who became one of the public faces of the UAlberta encampment, told the Orchard after reviewing the FOIP documents, referring to pro-Israel groups and the provincial government.

On Dec. 5, hours after the Orchard reached out to UAlberta for comment, the university released Justice Adele Kent’s third-party review of how UAlberta handled the encampment, which is dated Oct. 30.

Kent concluded that administration had intended “to bring a peaceful end” to the encampment, but said “potential dangers that arose made that impossible,” defending the decision to call the police as “a route that was legally available to the university.”

Student encampment organizers boycotted Kent’s review, citing its narrow, legalistic scope, which in her report Kent admitted made her “skeptical” that the issue could have been resolved through negotiation.

Over the summer, the Orchard filed a FOIP request with UAlberta requesting all correspondence sent and received by the university’s senior executive team regarding the encampment from the period leading up to its establishment on May 9 and dismantling on May 11.

The university provided 212 pages consisting largely of emails, but which also included multiple copies of the trespass notice campus security provided to the encampment, the operating procedures administration developed in response to the encampment and a text exchange.

Some of the email addresses were redacted, save for an “@ualberta.ca” domain, as was the entire content of many messages. The university opted to withhold 131 pages of relevant documents entirely.

The Orchard filed a FOIP request with a near-identical scope with the University of Calgary, where a pro-Palestine encampment was established the same day as UAlberta and disbanded that same night by cops in riot gear, but has yet to receive any documents.

Both encampments came amid a wave of similar actions at campuses across Canada and the United States, all of which sought to pressure universities to disclose investments, an increasingly important revenue source in the face of persistent provincial funding cuts, and divest from those profiting from Israel’s regime of Jewish supremacy from the Jordan River to the Mediterranean Sea. Protests had varying outcomes.

At the University of Windsor, McMaster University in Hamilton and Brown University in Providence, Rhode Island, university administrators agreed to meet some of the protestors’ demands, which resulted in the encampments being peacefully dismantled.

The University of Toronto encampment was permitted for two months before a judge issued an injunction ordering it dismantled in July, with which the organizers agreed to comply.

The encampment at McGill University lasted for 10 weeks before Montreal police and Sûreté du Québec officers, as well as private security contractors, took it down by force.

At the University of California, Los Angeles, police raided the encampment and arrested 200 pro-Palestine activists the day after pro-Israel counterprotestors physically attacked the camp, none of whom were arrested.

The UAlberta and UCalgary encampments, as well as one at York University in Toronto, stand out for their brief duration.

Based on the limited information UAlberta provided in its FOIP package and Kent’s report, what follows is an effort to piece together how administration reached its decision to dismantle an encampment that its own security team repeatedly suggested wasn’t a threat to anyone.

Day One

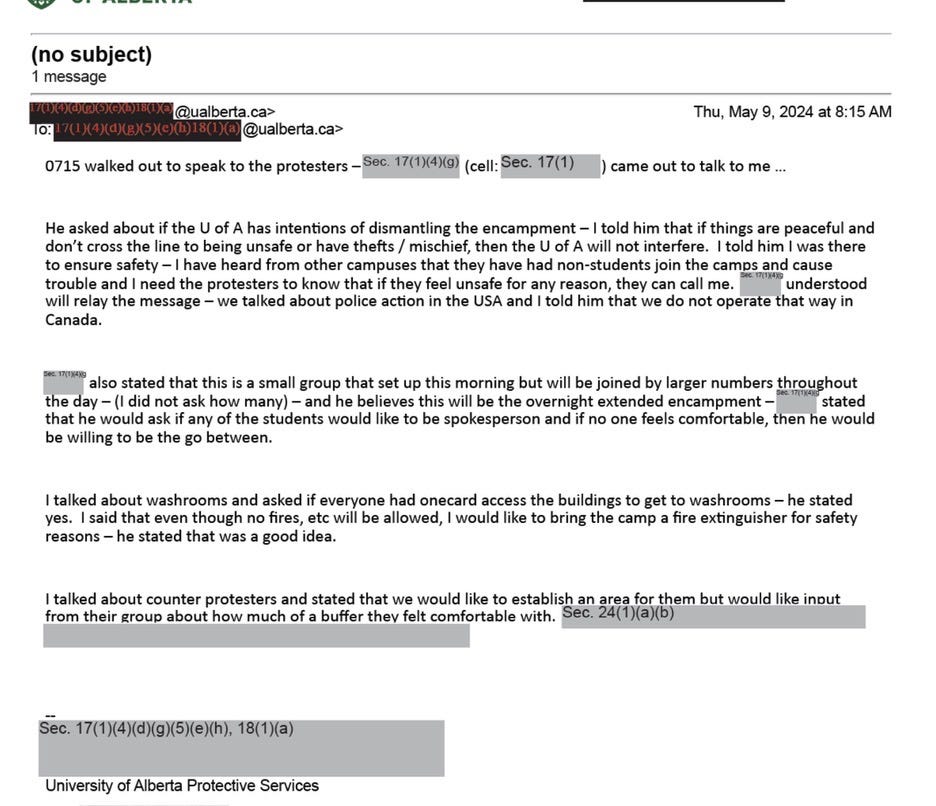

According to one of the emails obtained through FOIP, a member of University of Alberta Protective Services first visited the encampment, dubbed the “People’s University for Palestine,” on May 9 at 7:15 a.m., speaking to one of the “protestors.”

“He asked about if the U of A has intentions of dismantling the encampment — I told him that if things are peaceful and don’t cross the line to being unsafe or have thefts / mischief, then the U of A will not interfere,” wrote the campus security officer.

“[W]e talked about police action in the USA and I told him that we do not operate that way in Canada.”

They spoke of establishing an area for counter-protestors, “but would like input from their group about how much of a buffer they felt comfortable with.”

The Orchard showed the FOIP documents to David Kahane, a Jewish UAlberta political scientist who supported the encampment and was present for most of its duration.

He told the Orchard that Protective Services offered to put up fencing around the encampment, which the encampment leaders never seriously considered.

“The University of Alberta encampment, unlike most other encampments, was never barricaded. It was completely open to the surroundings,” Kahane added.

“Even people we knew to be unfriendly to the encampment could wander through the tents and go anywhere in the encampment.”

At no point, Kahane emphasized, did anyone from UAlberta administration show up at the encampment to discuss the students’ demands.

Justice Kent, in her report, cited unspecified “security concerns” that precluded administrators from going to the encampment, which she accepted at face value.

Also in the morning, someone from the university sent out a copy of a document entitled, “Operating Procedures Regarding Unapproved Demonstrations and Protests on University of Alberta Campuses,” which is included multiple times in the FOIP package, to Protective Services and the police.

The document, which was circulated more widely in the afternoon, suggests that, while unapproved events are by definition not permitted, they might be tolerated if they’re deemed “peaceful,” meaning they don’t violate any university policies against harassment, threats and intimidation, provincial and federal laws, or obstruct counter-protestors.

Other factors to be considered are “the degree of disruption” to campus life, “the suitability of the location relative to the number of participants, the length of the disturbance relative to its location, and the level of disturbance created by noise, tone of discourse, and other factors.”

According to Justice Kent, this document was drafted by administration and reviewed by the university’s legal team in the two days leading up to the encampment.

Although the Alberta Court of Appeal has determined that campus quads are public spaces, administrators have treated them as private property in need of protection.

At 9 a.m., the university’s Emergency Management Office held the first of three briefing sessions that day, the entire contents of which were redacted in the FOIP package.

But we know that there were around 20 members of UAlberta administration in attendance, including Jeanie Smith, chief of staff to president Bill Flanagan, deputy provost (students and enrolment) Melissa Padfield, university lawyer Brad Hamdon, vice-provost (equity, diversity and inclusion) Carrie Smith and dean of students Ravina Sanghera, as well as Shay Exner of the Emergency Management Office, among others.

The usernames of two participants with UAlberta email domains were redacted.

The second briefing occurred at 11 a.m., followed by a third at 1:30 p.m.

At 3:14 p.m., Const. Dan Tallack, the Edmonton Police Service (EPS) liaison to UAlberta, emailed other EPS officers and four redacted UAlberta email addresses confirming that security’s interaction with the encampment was “positive.”

“I will ensure all of you are made aware of any significant events or changes which may necessitate additional police involvement,” Tallack wrote at the end of his email.

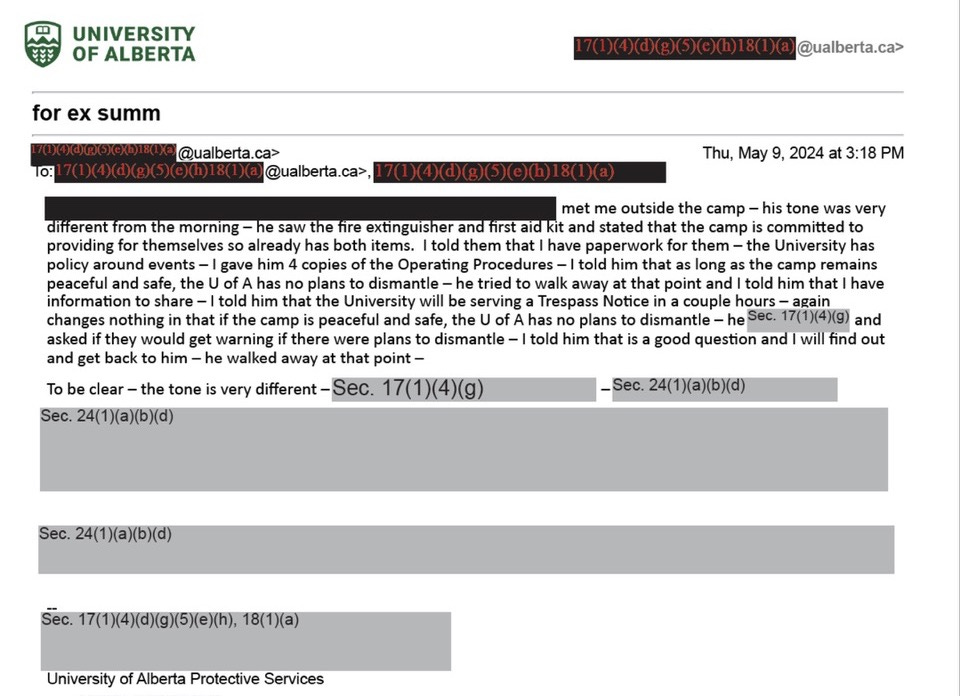

Minutes later, a security official met again with an encampment member, noting in an email that their “tone was very different from the morning.”

The security officer wrote that they brought a fire extinguisher, first aid kit and four copies of administration’s operating procedures to distribute among encampment participants.

The encampment protestor rejected the first aid kit and fire extinguisher, noting that the campers already had these items.

The Protective Services officer added that they had an important bit of “information to share”—that the university was planning on issuing a trespass order within the next two hours, but “if the camp is peaceful and safe, the University has no plans to dismantle [sic].”

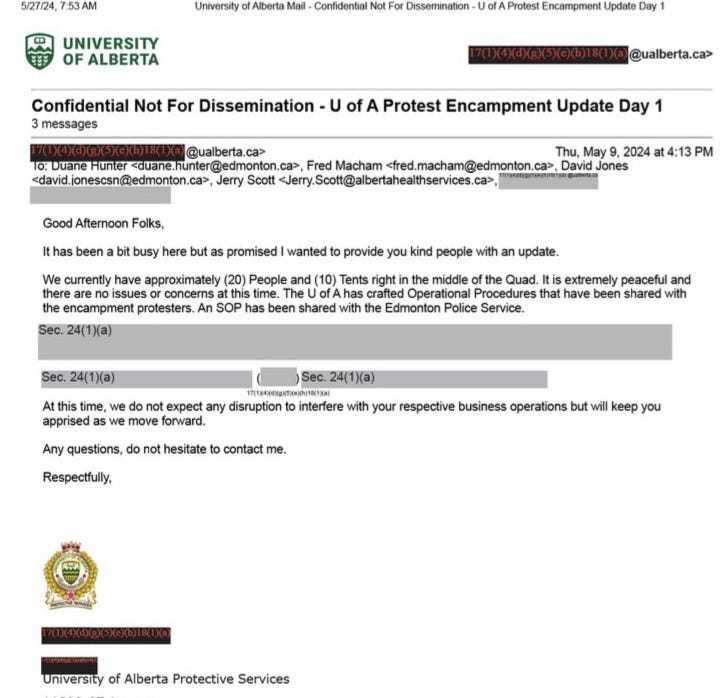

About an hour later, a member of Protective Services sent an email, labelled “Confidential Not For Dissemination,” to City of Edmonton director of transit safety Duane Hunter, operations manager of transit peace officers Fred Macham and chief bylaw officer David Jones, as well as Alberta Health Services chief protective services officer Jerry Scott and someone from UAlberta whose email is redacted.

Despite the perceived change in tone, the security staff characterized the encampment as “extremely peaceful,” noting that it consisted of about 20 people and 10 tents.

Abraar Alsilwadi, a Palestinian-Canadian sociology student at MacEwan who was involved with the encampment and also reviewed the FOIP documents, noted the sharp contrast between this description and “what the police tried to portray it as after the sweep.”

At 4:21 p.m., Flanagan sent out a public community bulletin, referring to “those who have chosen to demonstrate peacefully on our campuses” and vowing to “ensure [their] safety.”

“However, any action that impedes the university’s core business of teaching and learning—or violates the law or policies of the university—goes beyond the parameters of freedom of expression. In particular, the university will not tolerate hate speech or calls for violence,” he cautioned.

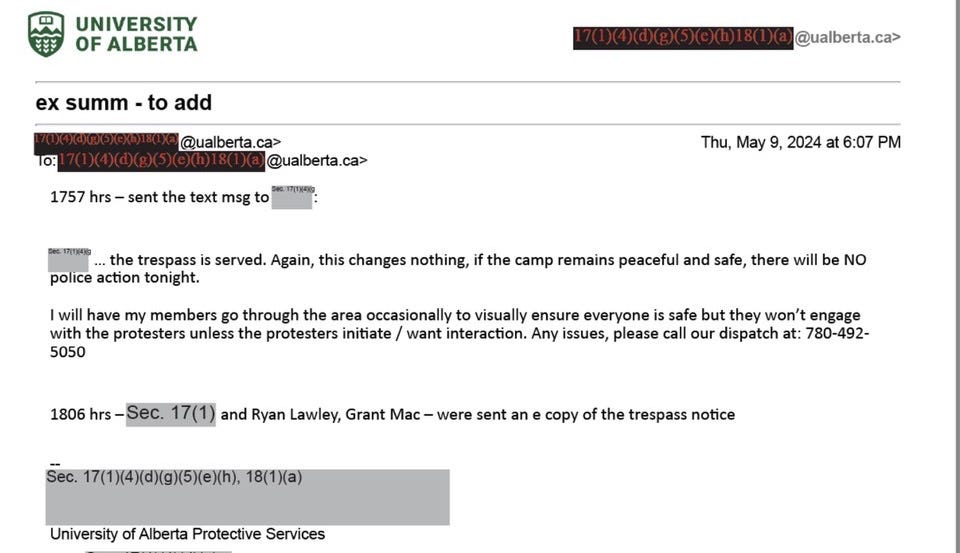

Just before 6 p.m., Protective Services issued a trespass order to the encampment and soon after forwarded it to their counterparts at MacEwan. By this point, CCTV footage indicated that the encampment had grown to 15 tents and 45 people, according to Kent’s report.

The trespass notice, which is included in the FOIP package repeatedly, warns students and faculty who decide to stay that they “may face student non-academic disciplinary action or employee disciplinary action, as well as potential arrest [emphasis added].”

“Again, this changes nothing, if the camp remains peaceful and safe, there will be NO police action tonight,” a Protected Services employee emphasized in an email sent to two UAlberta emails with redacted usernames.

At 9:21 p.m., Const. Tallack informed his EPS colleagues that campus security distributed the trespass notice to encampment participants.

Day Two

Unlike the encampment’s first day, the FOIP documents contain no indication that administration held any briefings on May 10.

By that time, Calgary cops had used force to dismantle the UCalgary encampment, a development which Salhi told the Orchard “raised the alarm for us a bit.”

“We were a lot more aware that that's a reality we could be facing soon,” she said.

At an unrelated press conference that morning, Premier Danielle Smith said she was “glad” the UCalgary encampment had been removed, insinuating that she would like to see the same occur at UAlberta.

“I’ll watch and see what the University of Alberta learns from what they observed in Calgary,” Smith told reporters.

In her report, Kent notes that a pseudonymous member of UAlberta’s external relations department had repeated conversations with Ministry of Advanced Education officials about the encampment on May 9 and 10, but accepted multiple administrators’ assertion that the government never directed their encampment response.

Meanwhile, campus security’s communication with EPS moved higher up the chain of command.

At 7:53 a.m. on May 10, Supt. Bart Lawczynski of EPS Operational Support Division emailed Protective Services “to open up some lines of communication as we get deeper into this Protest Encampment [sic] on U of A property.”

“[W]e were hoping to connect with you to begin to understand the path forward as we try and support you in resolving this.”

Someone at Protective Services responded about 20 minutes later, writing: “We are encouraged by your email and would love to connect today.”

Kent noted that EPS members met virtually with vice-provost Gilchrist, vice-provost Allen and chief-of-staff Smith from the university at 11:30 a.m. and told them that “bad actors” had infiltrated the encampment, although they didn’t identify any specific people.

Citing her interview with Gilchrist, Kent said administration made the “final decision” to call the police to campus to dismantle the encampment at some point after 1:30 p.m.—less than 24 hours after campus security called the camp “extremely peaceful.”

EPS didn’t acknowledge the Orchard’s request for comment.

There are just two emails in the FOIP documents that hint at why UAlberta might have changed its approach towards the encampment.

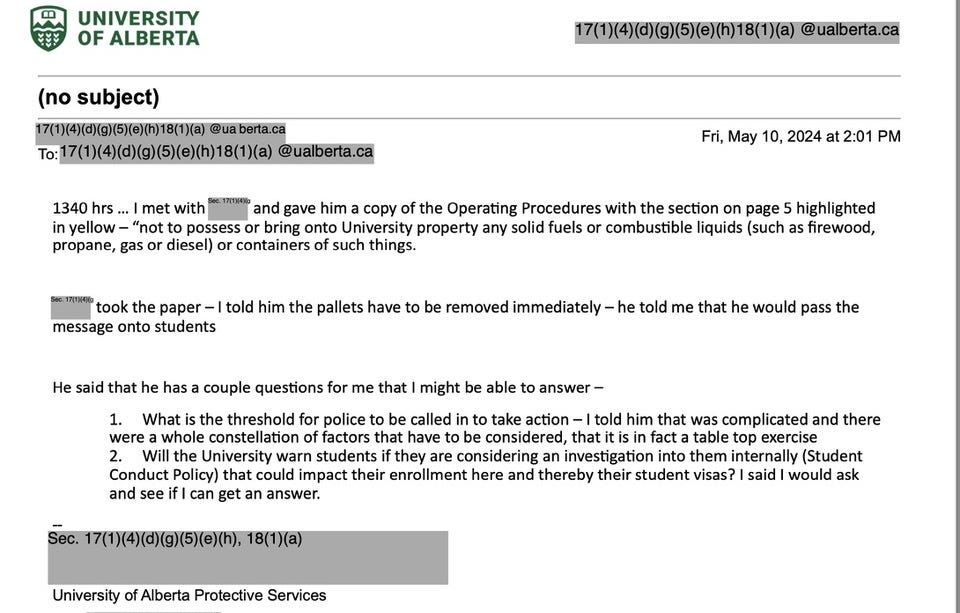

At 1:40 p.m., a Protective Services officer met again with an encampment member to tell them that wooden pallets had to be removed from the encampment’s premises, citing them as an example of flammable material that is prohibited.

President Flanagan cited the presence of pallets as a matter of “great concern,” owing to their potential to “to be used as barricade-making materials — actions that are counter to peaceful, law-abiding protests,” in his May 11 community bulletin providing post-hoc justification for sending the cops to tear it down.

He didn’t mention them being a fire hazard, nor did Protective Services mention anything about a barricade.

The purported dangers posed by the pallets were central to the justification Justice Kent accepted for tearing the encampment down.

“The thinking shifted because of the pallets,” she wrote. “The decision was made for safety reasons.”

But according to Kahane, Alsilwadi and Salhi, the pallets were removed from the encampment upon security’s request.

The pallets, Salhi said, were given to the encampment by supporters based on the understanding that the camp would be in the Quad until its demands were met, and were intended to protect tents and supplies in the event of adverse weather.

“But when it was cited as a hazard by security, of course, that wasn't the hill we were going to die on,” she said.

The security official noted two questions the encampment member asked after they issued a warning about the pallets:

What is the threshold for police to be called in to take action — I told him that was complicated and there were a whole constellation of factors that have to be considered, that it is in fact a table top exercise [sic]

Will the University warn students if they are considering an investigation into them internally (Student Conduct Policy) that could impact their enrollment [sic] here and thereby their student visas? I said I would ask and see if I can get an answer.

There’s no indication from the FOIP documents that Protective Services provided an answer.

That same afternoon, an email from an address that was entirely redacted was sent to associate librarian Denise LaFitte, with the subject, “Re: Anti-Semitic protest on campus.”

The person who wrote the email said they “saw some disturbing messages displayed at the encampment,” including “anti-Semitic displays with the wording ‘Jews…’ as well as mentions of Intifada, which is a direct call for violence.”

“Why does the UofA permit this on its grounds (it’s not free speech, it’s a [sic] hate speech)?” they concluded.

LaFitte didn’t ask any questions, writing, “thanks for letting us know. I will report it immediately” before forwarding the email to Protective Services.

In her remarks praising the police response at UCalgary that morning, Smith had raised the prospect of the encampments engaging in “hate crimes” and “antisemitism.”

Kahane said the only sign at the camp with the word Jews on it was a banner brought by Jewish encampment supporters, who organized a Shabbat dinner at the camp that evening, which read:

JEWS SAY:

CEASEFIRE NOW

LIFT THE SIEGE

END CANADA’S COMPLICITY

FREE PALESTINE

The notion that the word intifada, which simply meaning uprising or shaking off in Arabic, is an open call to violence against Jewish people is a common canard in pro-Israel circles, one which was echoed in a May 10 tweet from the Jewish Federation of Edmonton calling it “outright hate speech.”

In order for a statement to be hate speech under Canadian law, it has to reference an identifiable group of people.

Yasmeen Abu Laban, a Palestinian-Canadian political scientist at UAlberta who is the Canada Research Chair in the Politics of Citizenship and Human Rights, told the Orchard that the word intifada “does not reference any specific group or geographic context.”

“In a protest situation centring solidarity with Palestinians, people are typically using it to underscore the idea of resisting Israel's ongoing military occupation and human rights abuses,” she added, noting that resistance can be violent or non-violent.

There have been two Palestinian intifadas against Israeli occupation—the first occurred from 1987 to 1993 and the second from 2000 to 2005.

“The notion that the intifadas themselves were these pure moments of violence against Israelis, just because they're Jewish, is blatantly false [and] at best disingenuous,” Muhannad Ayyash, a Palestinian-Canadian sociologist at Mount Royal University in Calgary, told the Orchard.

While there were certainly acts of violence against Israelis during the intifadas, especially the second one, Ayyash said that characterizing them as purely violent obscures the “many unarmed actions that included general strikes, labour strikes and demonstrations by people of all ages” during both uprisings.

“What it refers to is a people's uprising, the idea of a people collectively saying, ‘Enough is enough, we want to be free,’” he said.

According to the cops, they were asked to come to campus to remove the encampment around 4 p.m., a few hours after Kent’s report said administration made the decision.

EPS claims that at its peak, the encampment included 150 people and 40 tents.

After issuing their final trespassing notice at 4:35 a.m. on May 11, police entered the encampment, which they claimed had dwindled to 50 people, chanting “move” in unison, hitting people with batons who stood in their way, and deploying what police called “special munitions,” which they later clarified consisted of pepper bullets and OC powder.

Given repeated re-assurances from campus security that the trespass notices were a mere formality, “we definitely did not expect to be woken up before dawn and brutalized by the cops,” said Salhi.

“It did come as a surprise, and looking back, it probably shouldn't have,” she added. “At the end of the day, these policing systems are just extensions of the broader colonial system.”

The cops arrested three people, whose charges were stayed by the Crown the following month.

Aftermath

At 7:46 a.m. on May 11, Flanagan sent out his aforementioned statement defending the university’s handling of the encampment.

“Over the past two days, we repeatedly informed the group of the procedures for demonstrations and protests on university campuses, both in writing and verbally,” he said, ignoring security’s repeated re-assurance that the encampment would be able to continue if it remained peaceful.

Based on the experiences of other unspecified campuses, Flanagan added, “we have witnessed how quickly they can escalate and become volatile.”

“Overnight protests are often accompanied by serious violence and larger crowds amplify those inherent risks — especially as they attract counter-protestors or outside agitators,” he wrote, ignoring security’s early efforts to establish parameters around counter-protestors.

Kahane said the spectre of counter-protestors was rooted in “paranoia and fantasy,” noting that there hasn’t been any organized counter-mobilization to weekly pro-Palestine protests in Edmonton at any point over the past 14 months.

Flanagan claimed that, “[t]o the best of our knowledge,” less than a quarter of encampment participants were actual students, but didn’t explain how he arrived at that figure.

Salhi said she can say with “full confidence” that Flanagan was lying.

“Whether they were students, faculty or alumni, the majority of the camp was U of A community, and otherwise it was a couple MacEwan students,” she said.

“If that's grounds to then send the cops to brutalize students, I don't know what to tell you.”

Flanagan echoed the cops’ claim that there were no injuries in the course of dismantling the encampment, but encampment organizers said there were four injuries.

The day of the sweep, the People’s University for Palestine YEG Instagram account posted an image of someone whose leg was bleeding after getting hit with a baton:

In an additional statement on May 12, Flanagan cited the presence of “potential weapons, including hammers, axes and screwdrivers, along with a box of syringes”—basic camping and harm reduction supplies—as evidence that the “encampment posed a clear and imminent threat to campus safety and security.”

“Had anyone been injured or killed, the responsibility for this would rest squarely with the university. Everyone would quite rightly demand: how could the university have done nothing to prevent this?”

After law professors at UAlberta and UCalgary wrote an open letter noting legal precedent for regarding “tents and temporary structures” as forms of Charter-protected expression, Flanagan issued a May 15 statement emphasizing UAlberta’s “foundational commitment to freedom of expression” while reiterating the same talking points about “safety.”

It took Edmonton police almost a week to hold a press conference on its handling of the encampment, in which Chief Dale McFee said that calling the cops was “probably a really good call” by the university.

Insp. Lance Parker claimed police were attacked first and that their show of force “was incredibly minimal.”

Deputy Chief Devin Laforce went as far to say that police were victims of “bullying, harassment and intimidation,” and that the fire extinguishers on site—which you might recall were offered to the camp by campus security—could be used to “blind and bludgeon” police officers.

“If we didn't have the fire extinguisher, they would have said it's a fire hazard to not have the fire extinguisher,” Alsilwadi noted.

On May 13, Premier Smith, who three days earlier praised Calgary cops for their UCalgary encampment sweep, ordered an Alberta Serious Incident Response Team investigation into how Calgary and Edmonton cops dismantled the encampments, citing reports of injuries in both cases.

Public Safety and Emergency Services spokesperson and former Western Standard scribe Arthur Green confirmed on Nov. 1 that ASIRT’s “limited scope investigation” had concluded and that none of the injuries were deemed “serious.”

In June, the UAlberta Board of Governors unanimously passed a motion to proactively disclose a complete list of the university’s endowed investments, soliciting the support of the Canadian Shareholder Association for Research and Education to review its holdings. MacEwan, however, has made no such promises.

Kahane said he’s “quite skeptical” of the UAlberta’s board’s stated commitment to reviewing its investments and that “continued pressure from the broader community” is needed to push them in the right direction.

“There is a whole world of responsible investment statements, consultants and principles that allow large investors to carry on doing basically what they're already doing, and so most often, those are window dressing,” he said.

On Sept. 19, the board released the past three years of the University Endowment Pool’s public equity investments.

Sara Carpenter, an education professor at UAlberta who is involved with Faculty for Palestine (F4P), told the Orchard that this list of companies only scratches the surface, because it excludes “information on the funds through which those equities are held.”

“They have also not disclosed the content or companies that manage funds in private equity, real estate, infrastructure, energy, or commodity investments, and have argued that they are contractually barred from public disclosure,” said Carpenter. “They have also not disclosed the non-endowed investment pool.”

But even with the limited information the university has provided, she said F4P has identified $143 million in investments with firms “that have been identified as active private sector participants in the illegal occupation of Palestine.”

At the same time he announced UAlberta’s new disclosure policy, Flanagan made a vague commitment “to exploring how we, as a university, can support Palestinian scholars and students displaced by this conflict and the rebuilding of Gaza’s universities.”

Meanwhile, in occupied Palestine, the situation is “still getting worse every single day,” said Alsilwadi, who has family in the West Bank and friends in Gaza.

“Displaced people continue to become even more displaced, going from one camp to another. Some don't even know where to go,” Alsilwadi said. “There's literally nowhere to go.”

With the onset of winter, Alsilwadi cited reports of people “dying of cold weather in their tents.”

“They’re losing all their stuff,” she said. “It’s like a living nightmare, honestly.”

In the West Bank, Palestinians rarely leave their homes due to the threat of increasingly emboldened extremist Jewish settlers, who have entirely eliminated 50 rural Palestinian villages since Oct. 7, 2023, when Gaza-based Palestinian militant group Hamas launched a surprise attack on southern Israel, killing and kidnapping hundreds of civilians.

“My aunt in Nablus hasn't seen her brother in Ramallah since the beginning of the genocide,” said Alsilwadi.

On the UAlberta encampment’s first day, Alsilwadi recalled showing a video of the Quad to her friend in Rafah, who expressed hope that the student movement’s momentum could pressure Western governments into halting Israel’s invasion of his city, which had provided the last refuge from ceaseless Israeli attacks.

Her friend has since been displaced to Khan Younis, a city which is mostly in ruins, after Israel proceeded with its Rafah invasion, manifesting a familiar sense of “extreme disappointment” among Palestinians.

“But the fact that there's a group of people that are still fighting and persist in screaming free Palestine, that at least puts a smile on their faces,” said Alsilwadi.

Edited by Roberta Lexier

Thanks for doing this, Jeremy! Really important work!

Thank you Jeremy. It's astonishing to see the revisionism on display from UofA administration, all in one place.