What's going on with the Communist Party of Canada?

Sexual harassment, a coverup, expulsions and many resignations

The Communist Party of Canada (CPC), the country’s second-oldest continuous political party after the Liberals, is not exactly a major force in Canadian politics.

In the 2021 federal election, the party received 4,700 votes, despite running on a strong social democratic platform with policies like free post-secondary education, a $23 minimum wage, decreasing the retirement age to 60, and immediate universal child care and pharmacare. This was an increase of 795 votes from 2019, but the 26 candidates they ran in 2021 were four fewer than in 2019. Still, it was the CPC’s best result since the turn of the millennium.

With crises on multiple fronts — climate, public health, LGBTQ+ rights, racial and income inequality — and, before entering an alliance with them, the NDP running ever-so-slightly to the left of the Liberals, now might seem like the opportune time for a Communist Party resurgence. The Party has bold policies the times call for, which are rejected out of hand by mainstream parties.

But instead, the party is facing a mass exodus of members, including some of its most prominent faces, after it was revealed that the Party had concealed a case of sexual harassment by one of its top organizers.

The defectors I spoke to joined the party because they thought it offered an alternative to the pro-corporate, pro-war consensus of the mainstream parties, but became disillusioned by what they describe as a sclerotic, out of touch leadership, which was more interested in protecting one of their own than building actual power. Each one remains a committed communist despite their decision to leave.

Party leader Liz Rowley says there’s no story here.

She claims that, while the party has lost members recently, it’s also gained some, though she declined to reveal any numbers. She also questioned whether those who left were committed to socialism to begin with. “We've been growing steadily for the last three years, and we still are. I know that some of the people who left are trying to make a big deal out of their departure, but people come and go. It's a political party. It's a free country,” Rowley told me.

Jack Adebisi first met Jay Watts in the summer of 2021 at a protest against state violence in Colombia when Adebisi was a member of the Young Communist League (YCL) — an organization in the same orbit as the CPC but not officially connected to it — and Watts was the CPC’s central organizer — a paid position. Adebisi was in their early-20s, Watts in his early-40s.

Adebisi, who is non-binary and Black, had recently moved from the U.S. to Canada to study engineering at Toronto Metropolitan University. During the pandemic, YCL events were their sole means of social interaction. They would see Watts at various events and would talk to him about Canadian politics, which was still unfamiliar terrain for Adebisi. They knew Watts had his demons, particularly a drinking problem, but figured they were something the Party would bring under control.

“We had similar backgrounds in terms of being abused in childhood, so I had seen him as a mentor,” Adebisi told me.

On Oct. 5, 2021, Adebisi and Watts were invited to a mutual friend’s house, where Adebisi found out Watts’s grandmother had recently died. At the end of the night, their mutual friend suggested Watts walk them to the subway station, since Adebisi was still somewhat unfamiliar with Toronto. Watts put his arm around Adebisi, and when it was clear they weren’t walking towards a subway station, they asked Watts where they were going. As soon as he was questioned, Watts changed directions and headed back to the station

Adebisi figured Watts’s strange behaviour had to do with his recent loss and didn’t think much of it until the next week, when they were at the same friend’s house again:

I pulled Jay aside because I wanted to ask him advice for something — an issue he knew about. Instead of giving me advice, he starts flirting with me and I'm confused about that. Then he touches me in my torso and I'm very uncomfortable with that, so I just excuse myself and go to the bathroom. And from the corner of my eye I saw him try to follow me towards the bathroom. I don't know how long I was in the bathroom, but when I came out, I saw him on the couch, and I thought he had passed out or something. So I'm just checking if he’s OK or not. I try shaking him awake. He grabs my hand and kisses it and as I'm trying to move away, he grabs it tighter, and I just didn’t know what to do.

Their friends said Watts was too drunk and called him an Uber, but Watts nearly refused to get in his ride until he saw Adebisi again.

A few days later, Adebisi went to a bar after hanging out at Party HQ and, when the night was over, some Party members suggested Adebisi and Watts catch a ride home together since they lived near each other. Watts repeatedly propositioned Adebisi while they waited for their Lyft, trying to convince them to come home with him. “Come on, I know you just want to get your dick wet,” Watts told them before kissing their hand, just as he had done a few nights before.

The next day, Adebisi told the YCL’s general secretary Ivan Byard what happened, and Byard assured them the party would launch an investigation. In the meantime, Watts texted Adebisi to apologize on Oct. 19, acknowledging his behaviour was out of line and promising not to contact them, nor anyone else in the YCL, again.

Adebisi said they weren’t kept in the loop of the Parrty’s investigation and had to repeatedly inquire about its results. They later found out Watts was supposedly suspended from the party for three months, demoted from his position, forbidden from being near YCL members and encouraged to get help for his excessive drinking.

But Adebisi soon discovered these terms weren’t enforced. He stopped by Party HQ in March 2022 and saw Watts there, in the presence of YCL members, freely speaking to other party members. Watts was even asked to take a photo of YCL members putting up posters for an upcoming rally. “It felt very much like I had gone through all of the stress to tell them this horrible thing had happened to me and they just moved on like nothing had happened,” Adebisi recalled.

Adebisi sent a letter to the Party executive in May, which resulted in a June 15 meeting with Party leadership, including Rowley, who retraumatized Adebisi by asking them to point specifically to where Watts touched them. Adebisi was also informed they wouldn’t have the opportunity to bring their concerns to the Party convention, since they are technically a member of the YCL, not the CPC.

The Party leadership said it simply “forgot” to tell the Parkdale club, of which Watts was a member, what he did, despite Adebisi having requested they do so in their May letter and at the June meeting.

This is when Adebisi reached a breaking point:

I just realized they didn't care. They didn't care what Jay did. They didn't care how it affected me. They didn't care about how it put other vulnerable YCL members in danger, because we have high school members in the YCL, we've got people who just started university in the YCL. It's comfortable letting people join and knowing they were with someone that had done that to me.

The following day, Adebisi decided to make their concerns public through a statement on Twitter, which was at the time an anonymous account. Two days later, they called on the CPC’s central leadership to resign, this time signing their name, since the CPC had outed their identity in an internal memo.

Watts resigned from the Party of his own volition on June 21. Reached by email for comment, he said: “I’m good, thanks!”

Four prominent CPC members were expelled for their outspoken defence of Adebisi and their criticisms of how the Party handled Watts’s behaviour. Kiran Fatima, who joined the CPC five years ago out of frustration with the NDP’s increasingly milquetoast trajectory, is one of them.

Fatima’s interest in the Party was piqued by a conversation with other Pakistani-Canadians who were Communists. “That was something new for me. I had never known people like that existed anyway. That kind of pulled me into the Communist Party's orbit,” she recalls.

After a trip to Cuba, Fatima dove headfirst into the Party, joining the executive of the Parkdale club and sitting on various committees, all with the Party’s encouragement.

Politically, she’s had misgivings over the Party’s support of a two-state solution to the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, which, at least on paper, is identical to those of the Liberals and Conservatives, and its refusal to explicitly acknowledge Canada as a settler colonialist project — both of these concerns were expressed by multiple former members I spoke to.

Fatima knew Watts fairly well, as members of the same club, and was aware of his proclivity for getting shitfaced. “I saw it getting worse over the years that I knew him,” Fatima, who is a podcaster and streamer, observed. “This party has a huge drinking culture.”

For Fatima, the seriousness of the issue was in Watts taking advantage of Adebisi’s vulnerability as a young, Black, queer person who had just moved to town and was relatively new to Communism. “It's not just a matter of somebody hit on somebody and they didn't like it. It's that they had almost like a teacher-student kind of relationship, that kind of power dynamic,” Fatima told me.

According to the Party’s constitution, when a member is disciplined the Party must inform their local club. This never happened, Fatima said. Instead, central committee told Watts to tell his club what occurred, allowing him to spin whatever narrative he wanted.

“He told us that he was going back home to B.C. and he was on medical leave from the Party's position to get help for his drinking,” she recalled.

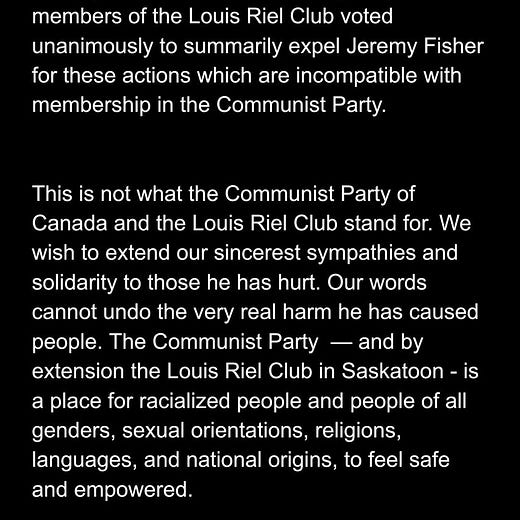

By contrast, when former Party member Jeremy Fisher’s penchant for sending unsolicited lewd texts to young women was revealed online, his Saskatoon club was notified and their own local executive made the decision to expel him.

Fatima found out the true nature of what Watts did — which he admitted when the Party slapped him on the wrist — the same way everyone else outside the central executive did: on Twitter. She decided to speak out in part because it appeared she and other members of the Parkdale club had protected Watts, when in reality they didn’t know what specifically happened.

Once she and other prominent Party members — Q. Anthony Omene, Nigel Cheriyan and Mike Oldfield — began speaking out, Rowley countered by “slandering the shit out of us,” Fatima said. Rowley accused them of leading a “Colour Revolution inside our party — an inside job.”

Rowley’s “Colour Revolution” letter outed deadnamed Omene, and misspelled both his and Adebisi’s names, demonstrating the degree of thought and care that went into her communications. ‘Colour Revolution’ refers to covert U.S. efforts to overthrow governments it didn’t approve of in the early-aughts, a comparison which is silly enough, but it’s a uniquely poor choice of words when one considers that three of the four members expelled — Fatima, Omene and Cheriyan — are racialized.

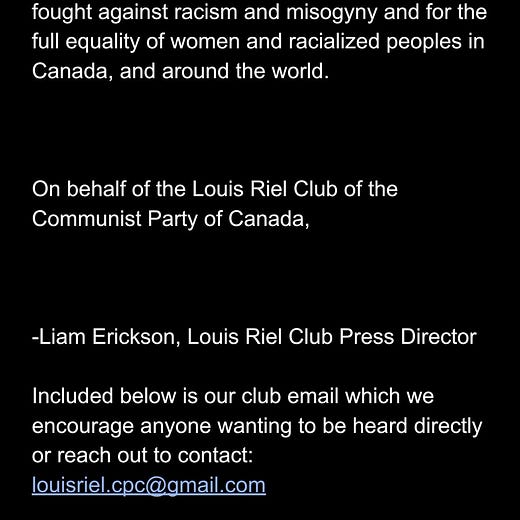

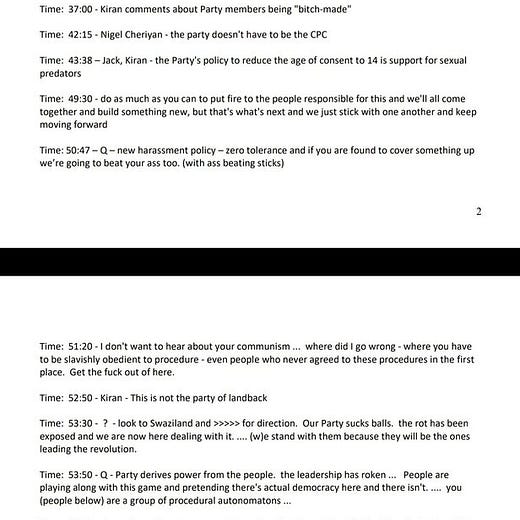

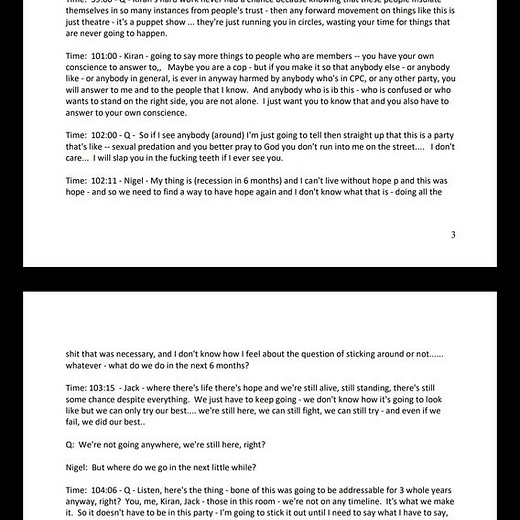

On June 25, Fatima, Omene, Cheriyan and Oldfield were officially expelled from the Party, using their remarks in support of Adebisi in a Twitter Spaces chat as evidence against them, standing in stark contrast to the kid-gloves treatment of Watts.

The week before her expulsion, somebody pointed Fatima towards a plank in the Party’s 2015 platform, calling for the age of consent to be lowered to 14 from 16, which would have been a major red flag had she known about Watts and the Party’s inaction.

All of these issues are part of a broader malaise within the Party, Fatima said. Former members like herself thought they were joining the venerable party of Dr. Norman Bethune, but ultimately it’s Liz Rowley and her friends’ personal fiefdom.

“There's a … lack of transparency in the Party,” she said. “Basically the party has operated as a very close circuit like a clique of just a few people. The growth that they experienced in the last couple of years has been overwhelming. In fact, I've been told by several of them that it's scary. They're actually discouraging people from joining.”

The Party doesn’t share its membership figures, but many of the former members I spoke to described significant growth over the past several years.

As justification for their expulsions, Fatima, Omene, Cheriyan and Oldfield were accused of the f-word in Communist circles — factionalism, or splitting the Party.

Omene, whose work you might have read in the Globe and Mail or Macleans, told me this is a gross misreading of what ‘factionalism’ actually means. “In order for it to be factionalism, I would have to be pushing a different political line aside from what the party openly supports,” he explained. “So what political line am I putting forward that is different from what the party has put forward?”

Omene said he supports restorative justice, but the CPC’s lax treatment of Watts isn’t “remotely close to what restorative justice looks like.” “I'm not saying that the Party should have just canceled Jay and made him socially dead,” he added, but there is a middle ground between letting an admitted sex pest do whatever they want and ostracizing them for life.

Omene outlined what he thinks the Party leadership should have said:

Hey listen, Jay, you can't stay on as central organizer, you're going to be suspended from the party based on this. Having found that you conducted yourself this way, please go get some help. At whatever point you feel that you've been able to make sufficient amends, we're open to you rejoining the party.

Instead, central leadership attempted to conceal it, which Omene said reflects a “senescent leadership” that is stuck in the past and unwilling to adapt.

Like others I spoke to, he respects Rowley, as well as former leader Miguel Figueroa, for pushing back against elements who, after the Cold War, wanted to take an anti-Stalinist line, which they argued would turn the CPC into just another bourgeois party.

“But when it comes to dealing with things like sexual harassment no, I'm sorry, that's not something that has anything to do with revisionism,” Omene said.

“It is simply acting in the best interest to preserve the integrity of the party. Who's going to want to join a party where people can just do shit like that?”

It’s not as if the leadership’s existing approach has been successful, he added. Try asking a working class person who the leader of the Communist Party is. “They would never be able to fucking tell you,” he said. “How do you in any way represent the working class that they don't even know who you are?”

Dock Currie doesn’t think what Watts did was that big a deal, but he concedes his perspective is coloured by his aspirations to be a criminal defence lawyer. He also acknowledges Watts is an old friend of his.

“My initial response was that the actual allegation disclosed -- two instances of sexual solicitation over five days, in a social setting, between two adults -- was pretty mild,” he told me via Twitter DM, adding that he was “gutted” by the whole situation.

Currie, who is a member of a club in Victoria, B.C., said calling the executive’s actions a cover-up is a “mischaracterization” and part of “the set-in-stone talking points of people who feel — rightly or wrongly — aggrieved by the party.”

To Currie, the party has been split between “people who earnestly feel like they were just standing up for a victim of inappropriate conduct and … those who don't feel like Twitter should be the ultimate clout venue,” dismissing Adebisi’s call for the entire executive to resign as an unrealistic demand, which has “hardened hearts and minds on all sides.”

He admits that “while it would have been well-advised” for Watts to tell the Parkdale club about the nature of the allegations against him, “there is no formal necessity that it be so transmitted.”

This isn’t true. Article 3, section 2 of the CPC’s constitution says that when a member is accused of wrongdoing, their “club shall inform the next higher level of the Party, and a higher body shall communicate the charges to the individual’s club [emphasis mine].”

While Rowley was unwilling to speak to me at length, Alberta Communist Party leader Naomi Rankin did. So what does she say about allegations of a coverup?

“Yeah, well, anybody can go on Twitter and say anything they want,” Rankin said. “A firestorm of allegations doesn't prove anything.”

She conceded that mistakes were made regarding how the issue was communicated but said the members who were expelled were perpetuating “this whole mythology about the evil Communists” and engaging in a “hate campaign and a mob justice campaign.”

The members who resigned in solidarity? “They were vulnerable to being triggered,” Rankin said, suggesting they were being manipulated by the members who got booted. “I'd make a real distinction between people who are genuinely upset from people who are deliberately fomenting stories.”

Who is fomenting stories? She wouldn’t name names, but did say she did accuse certain ex-members of using allegations of a coverup to launch lucrative media careers as professional ex-Communists, in an apparent reference to Omene and Fatima, who are both media figures with sizeable followings.

Rankin said she has faith that many of the members who left will see the light and come back into the Party fold. The CPC is in the process of creating a new sexual harassment policy, she added.

“It's unfortunate,” she said. “I wish it hadn't happened. But it doesn't change the fact that our party is the party of the working class. We're interested in socialism. We're interested in putting it into all forms of exploitation and oppression.”

Brandon Canning, a former member of the Hamilton club, said he was radicalized during the pandemic. The NDP’s support for the Liberals’ Canada Emergency Wage Subsidy, which gave money to bosses to pay employees’ wage, was the final straw. “This whole thing is bullshit,” he recalls thinking, “so that really kind of made me just look for other alternatives.”

He also wanted to find a way to confront the growing far-right in Hamilton, as well as globally, and who has more experience fighting fascists than Communists?

Canning joined the Party in autumn 2020. “When I joined the Communist Party of Canada, I honestly intended to die a member of the Communist Party of Canada,” he said. “For me, it was a very serious thing. It was like, this is how I’m going to organize my life. The idea of leaving was really hard.”

He didn’t have any major misgivings with the CPC until June 16 — when Adebisi went public. Canning had heard there were some allegations against Watts a few weeks prior but wasn’t informed of their specific nature. At first, he thought they could seek justice for Adebisi within existing Party channels, but the more he learned about Adebisi’s case, the more it became apparent this wasn’t a possibility. Adebisi had already gone through existing channels.

“They literally tried everything. They literally did everything right by the book, and it still didn't work,” Canning said.

Canning sat on the executive of the Hamilton club, which called for the resignation of the central committee leadership on June 22. He recalls the attacks on him and his comrades’ integrity beginning “pretty abruptly.”

Rowley made the rounds of Zoom meetings with the various clubs, arguing that those calling on her to resign were plotting a coup, trying to install themselves in power. She also alleged some might have been working with law enforcement to do so.

Like many members who eventually left the CPC, Canning held out hope that the Party leadership would accept their criticisms at their early-July national convention and acknowledge the need for a major overhaul. He would be sorely disappointed, as Rowley and her comrades were able to control the narrative on the convention floor.

Over the past two years, the Hamilton club had sprouted from just a few members to over 20. Now it remains in tatters.

Elliott Cooper, who was a member of the London club, describes an “intensely paranoid environment” at the party convention. Leadership seized members’ phones, because they feared proceedings would be recorded and distributed, but allowed members to have their devices back during lunch.

On the third day, Rowley announced she had received reports of people sharing information from the convention floor and would thus be forbidding members from accessing their phones all day.

As convention took place, members from across the country resigned en masse, including half of the Party’s Halifax club. “Suddenly we've got people getting up and saying new members aren't being vetted strongly enough, people aren't being developed into real Communists, we actually shouldn't let people join and we should be stricter about who we let in,” Cooper recalled. This isn’t exactly a way to grow a Party.

When he went to the Ontario convention the year before, he noticed a joyous atmosphere, with a Party ready to take on the world, boasting of new memberships, which couldn’t have been a stronger juxtaposition with the dreary atmosphere at the national convention.

E.P. was the only person I interviewed in person for this piece, meeting her at a downtown Calgary sandwich shop. (I had the tuna melt, in case you’re wondering.) I’ve agreed to refer to her by her initials so she doesn’t get fired from her job for being a Communist.

She likened the way the CPC operates in its present form to a cult. “There's a lot of commonalities, a lot of behavior where if you do something against a cult and you're ostracized forever,” E.P said. “There are people who feel like they've been thrown out of Scientology with this freaking party, which is in and of itself antithetical to Communism.”

Like many I spoke to, E.P. was drawn to the Party because of the failures of mainstream parties and the CPC’s brand recognition. She had no illusions about its shortcomings, such as the leadership’s insular worldview and technological illiteracy, but she saw these as relatively minor deficiencies that could be fixed from within.

“I tried hard to recruit good people and to help those who needed it. I had heard things about people in the party being like that pesty, but because the party dismisses everything as just like the handiwork of enemies, I had just brushed that off,” she said. “I was very eager to accept that, ‘no, this isn't true about the party.’”

Like most others, Twitter was the first place she heard about Watts’s behaviour towards Adebisi. She immediately empathized with Adebisi, but was also concerned with how this would reflect on the Party. “I could really see myself in their place,” E.P. said. “You're just an idealistic young kid. You want to make a better world, so you try and join a party.”

She and other members of the Calgary club held out hope that matters would resolve themselves at convention. Evidently, that didn’t occur, so they quit during a video call followup with Rankin, with members posting their pre-written statements in the call’s chat. It wasn’t an ideal decision, but was better than staying in what they regarded as an abusive relationship with the CPC.

So what’s next for all these communists across Canada who are now without a Party? I asked just about every person I interviewed this and none of them knew.

E.P. suggested perhaps the future of Communism lies outside a party structure. What’s the point of working within a system that is inherently hostile towards the Communist project?

She pointed out that the Party dismissed some clubs’ efforts to do mutual aid work, like the Hamilton club’s community fridge, as “Red charity.” But these sorts of projects are precisely how they can reach the masses. So in a sense, the implosion of the CPC frees its former members to make material impacts on people’s lives.

“We're going to try to do local organizations of various sorts and coordinate with each other country-wide, so that we can give each other help and advice, and share successes and failures,” E.P. said. “We can do for each other what we hoped the party would do for us.”

Edited by Roberta Lexier