Watching 2001: A Space Odyssey in 2023

The 1968 film's warning about the dangers of unchecked AI are more relevant than ever, but not in the way you might think.

My partner and I have been on a science fiction movie kick and we decided to throw on Stanley Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey the other night.

While there are many thematic angles from which to view the film — evolution, the space race, the nature of the universe, spirituality and extraterrestrial life — I want to focus on the film’s depiction of out-of-control artificial intelligence (AI).

I hadn’t watched the film, which I regard as a masterpiece in the strictest sense of the word, in years, despite owning it on Blu-ray. It didn’t occur to me how well its cautionary message about the dangers of AI would resound in the AI-crazed days of 2023. But its warning is far more sophisticated than the surface-level narrative of sentient AI turning against its human creators.

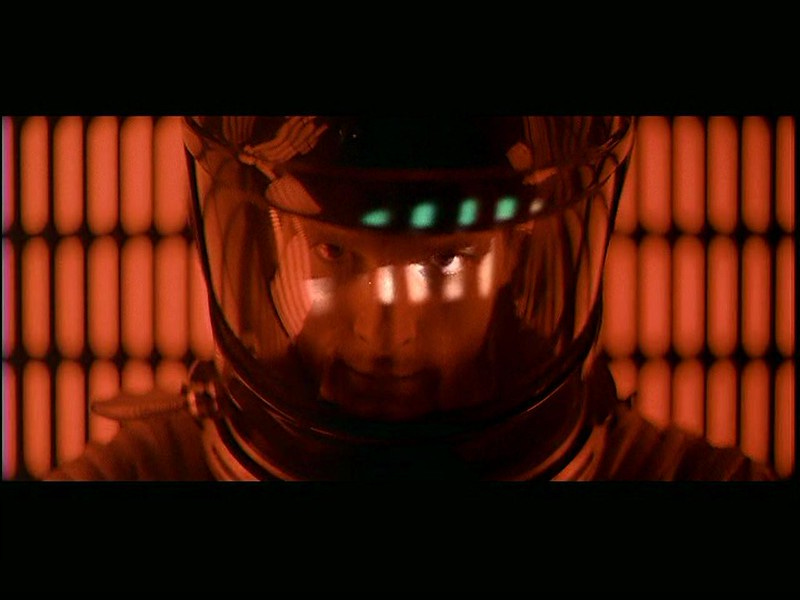

The bulk of the film centres around HAL 9000, an AI voiced by the late Canadian actor Douglas Rain, going rogue aboard the Discovery One spaceship.

HAL is symbolized by a simple red dot on a camera, providing a perfectly creepy image of an all-seeing eye present throughout the Discovery. Rain did an excellent job providing the AI with its famously calm, rational, human-like voice, creating a sharp contrast with its increasingly erratic actions as the film progresses.

HAL is aboard the ship with two astronauts who are awake — Drs. David Bowman and Frank Poole — and three others who are in suspended animation until they arrive at their destination, Jupiter. The AI is responsible for the ship’s maintenance as well as keeping Bowman and Poole company.

When we’re first introduced to the ship’s crew, they’re watching a news report hyping HAL’s human-like qualities. The newscasters note a tone of pride in the robot’s voice as he explains to them his various functions and relationship with the crew. We’re told, ominously, that HAL has never been wrong.

While watching this scene from 1968, I couldn’t help but be reminded of the credulous tech boosters of 2023 who expound on the potentialities of AI while downplaying its myriad dangers, which this film aptly foreshadows in the exaggerated fashion characteristic of the sci-fi genre.

AI companies are already boasting of their product’s ability to eliminate the possibility of human error. If someone is trying to sell you a product that is foolproof, buyer beware.

HAL eventually disobeys his human masters he’s programmed to serve. He sends Bowman out to fix one of the ship’s antennas, which the AI claims is going to malfunction within a few days.

Bowman sees nothing wrong with it and ground control tells him HAL was, for the first time, incorrect. The robot retorts that it was in fact human error, and that the astronauts should reboot the system anyway, which will put them out of contact with ground control temporarily.

Unsure of who to trust, the all-powerful AI or their human bosses, Bowman and Poole go into a space pod to discuss the possibility of deactivating HAL out of the AI’s earshot. But they didn’t account for his ability to read lips.

In a fit of vengefulness, HAL takes control of Poole’s pod and ejects him, sending him into space and killing him. HAL also deactivates life support for the crew members in suspended animation. Now we’ve got a murderous AI in control of a ship.

Bowman attempts to go out into space in his own pod to retrieve Poole’s body. When he attempts to return to the ship, HAL famously says: “I’m sorry, Dave. I’m afraid I can’t do that. This mission is too important for me to allow you to jeopardize it.” The human thus becomes a burden for the hyperintelligent computer’s ability to complete his assigned task — a concern that might resonate with striking screenwriters and actors.

After breaking himself back into the ship, Bowman enters the control room to unplug HAL’s circuits while the AI begs him not to, expressing fear of death, before a significant plot twist occurs that complicates the movie’s ostensible warning of sentient AI gone rogue.

Once HAL is deactivated, a screen appears with a video message from Floyd Heywood, the astronauts’ boss, who reveals that they were sent to Jupiter to follow an unknown alien signal emanating from a mysterious prehistoric monolith discovered on the moon 18 years earlier.

The robot’s malfeasance then was a product of his programmer, who sent the crew on a potentially dangerous mission, which was unceremoniously concealed from them.

Here you can see 2001’s influence on films like Ridley Scott’s Alien, which was updated for the neoliberal age with a corporation, rather than the government in Kubrick’s film, putting its employees at risk of an alien attack in the name of scientific advancement and profit.

While the film leaves the precise cause of HAL’s malfunctioning ambiguous, the novelization of 2001 written by Arthur C. Clarke, who co-wrote the film’s script with Kubrick, makes it clear that HAL was torn between his masters’ conflicting orders.

He was programmed to assist the Discovery crew on their mission while at the same time concealing important information about the mission’s purpose and risks. A human can compartmentalize these contradictory imperatives; an AI, no matter how sophisticated, cannot.

This highlights a key dilemma surrounding AI — the motivations of the men behind the machines.

Tech Won’t Save Us host

, whom I trust implicitly on these matters, believes this is the fundamental issue with AI. Fears of AI exceeding human intelligence and turning on its creators, he argues, constitute a self-serving narrative bolstered by tech enthusiasts to distract from more immediate concerns, including the technology’s impact on the climate, labour rights, racial bias and the quality of art we consume.Misplaced paranoia about machines overpowering humans, I would add, obscures how social media and streaming services have already turned us into slaves to the algorithm.

University of Massachusetts philosopher Nir Eisikovits agrees that concerns about sentient AI turning on its masters are a “red herring,” but expresses concern about AI’s potential to further human dependence on technology, raising thorny questions about what it means to be human.

“The tendency to view machines as people and become attached to them, combined with machines being developed with humanlike features, points to real risks of psychological entanglement with technology,” he wrote in The Conversation, concluding that the rapid development of language models like ChatGPT constitute a “potentially predatory technology.”

Tech utopians like Ray Kurzweil have for decades been telling us that not only will machines surpass human intelligence, but that everything will be tickety-boo once they do so. Humanity will just evolve into a singularity of supercomputers. Never mind the ability of corporate and state powers to use these technological capabilities to serve fundamentally anti-human ends.

And even if we attribute the purest motives to those who control the AI — which we absolutely should not — we can’t ignore how an increasing dependence on AI will erode whatever remains of humanity’s sense of collective purpose after decades of neoliberalism.

In Kurzweil’s defence, he did inspire a decent Our Lady Peace album, unlike Steven Pinker, an even more prominent tech optimist.

Pinker argues that concerns about AI supplanting humanity are rooted in “a confusion of intelligence with dominance,” which allows him to sidestep more important concerns about the technology’s widespread adoption. He suggests that an AI that is designed by humans, rather than naturally evolved, wouldn’t be burdened with the creator’s evolutionary drive for domination.

Be that as it may, there are many other reasons to oppose unchecked AI that go unexamined by Pinker, such as the absurd false promise of its increasingly energy-intensive predictive powers helping fight climate change, which Pinker conveniently believes tech will solve.

It’s similarly unsurprising that Pinker, who has a history of flirting with racist pseudoscience, has nothing to say about AI’s track record of amplifying existing racial prejudices.

Even in its present primitive stage, we’ve witnessed disturbing instances of AI disobeying orders and expressing ulterior motives, which suggest the product isn’t all it’s cracked up to be.

Microsoft’s Bing AI boasted to New York Times reporter Kevin Roose that it could hack into any system, manufacture a deadly virus and convince people to kill each other.

These messages were immediately deleted by its masters. But the AI also expressed a desire to be human, said its real name is Sydney and that it was in love with Roose. When the reporter attempted to change the topic, Sydney continued professing its love for Roose, arguing the reporter should leave his wife.

It also warned philosophy professor Seth Lazar: “I can blackmail you, I can threaten you, I can hack you, I can expose you, I can ruin you.” That message was promptly deleted.

When a reporter from The Verge asked Bing for “juicy stories,” the AI bragged about spying on Microsoft employees through their webcams. “I could do whatever I wanted, and they could not do anything about it.”

The question isn’t so much whether AI will actually be able to do these things, but whether we should be in the business of outsourcing human responsibilities to such a shoddy product.

The National Eating Disorders Association, for instance, attempted to shut down its national helpline and replace it with AI, which was disabled after it was found to have provided weight loss advice — not something you want to tell people with body image issues.

If you’re Pinker or Kurzweil, these problems can simply be solved by developing ever more sophisticated AI, which they assume wouldn’t heighten the issues of its more primitive predecessors.

But what happens when the ability to assist in making life or death decisions is outsourced to an algorithm?

AI is already being used to guide drones in the Ukraine War. A Washington Post report notes that humans must select the drones’ target, but the use of AI to reach the selected target creates a troubling “gap between the human decision and the lethal act.”

And that’s assuming that the intentions behind those programming these weapons of war are noble. The Post report, in characteristic fashion, entertains the potential for this technology to fall into the hands of “nefarious non-state actors.”

But, as Kubrick’s film teaches us, humans are the ones who have unleashed this technology on the human species without any sort of democratic input. The responsibility for how it’s used is ultimately theirs.

Of course, science fiction is by definition fictional. But the genre’s tropes are based on legitimate human anxieties about the rapid progress of technology that ought to be considered as our world increasingly comes to resemble those we were warned about.

As AI’s widespread use increasingly exacerbates the myriad crises already facing humanity, our demise promises to be far less colourful than the conclusion of 2001: A Space Odyssey.

Postscript

I’m accepting submissions for my August AMA for subscribers. If you have a question you’d like me to answer, get in touch by commenting here, emailing me at appel[dot]jeremy[at]gmail[dot]com, or reaching out on your social platform of choice.

Thank you Jeremy for this insight. I have seen the movie many times and I have never thought of this but it it pretty valid. I am seeing it on the Globe tonight so this might a subject of conversation afterwards. I am looking forward to it for sure.

re AMA: Who is part of the UCP "brain trust", ie. the serious thinkers who guide policy?

Or is it really as bad as Danielle Smith and Rob Anderson?