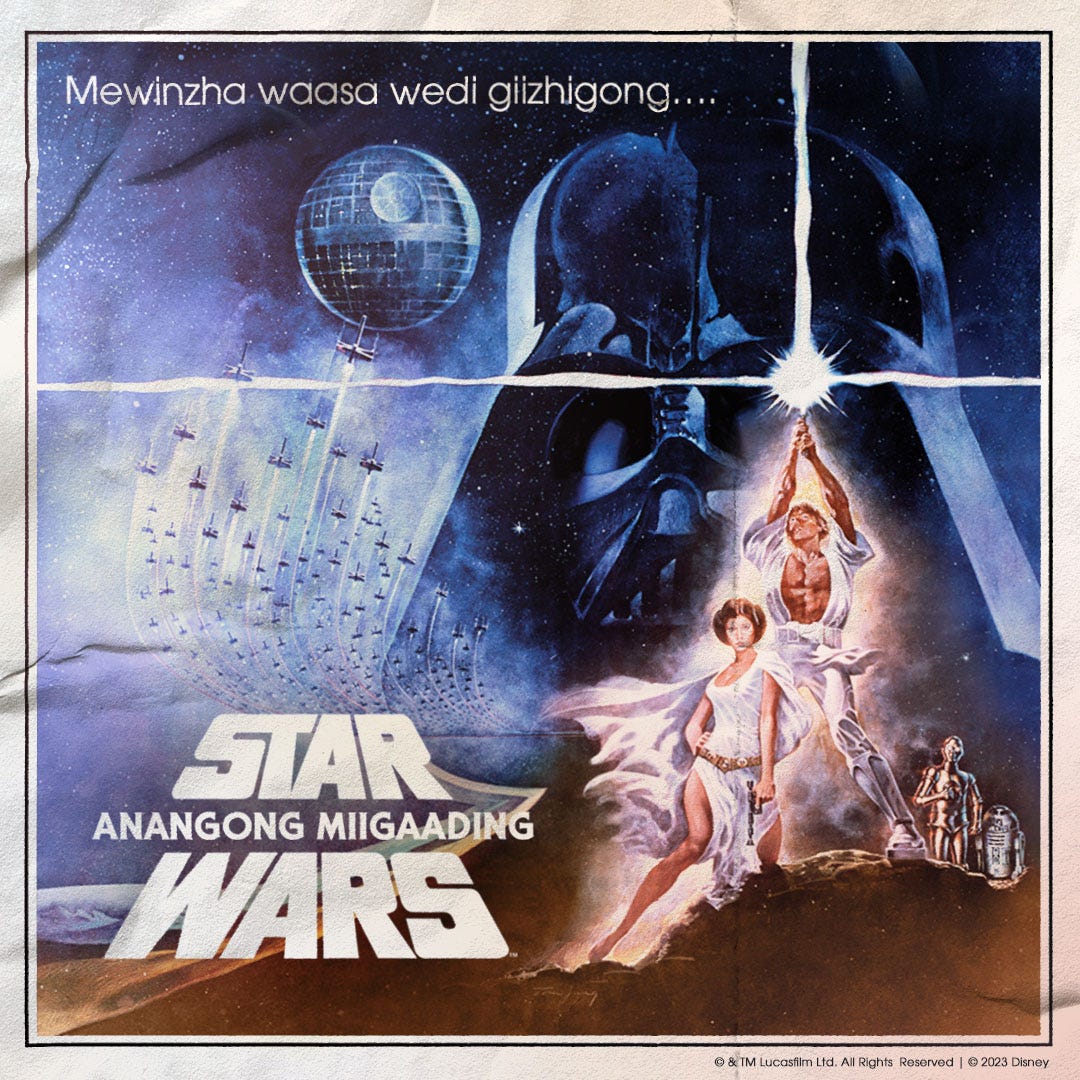

Ojibwe Star Wars premieres Aug. 8

The second Indigenous language adaptation of the classic film debuts at a special Winnipeg screening before a limited theatrical release.

This story was originally published in Alberta Native News.

An Ojibwe-dubbed version of Star Wars: A New Hope, the film that started the Star Wars franchise in 1977, is coming to select big screens in August, marking the second occasion the iconic film has been translated into an Indigenous language.

Anangong Miigaading, the Ojibwe, or Anishinaabemowin, translation of Star Wars will premiere at Winnipeg’s Centennial Concert Hall on Aug. 8, with a limited release in Winnipeg and other select markets starting Aug. 10.

Afterwards, it will air on APTN and be available to stream on Disney+, but those dates have yet to be revealed.

In December, the Dakota Ojibway Tribal Council and University of Manitoba announced that they entered a partnership with Disney/Lucasfilm and APTN to adapt an official Ojibwe version of the first Star Wars film, with auditions for voice actors occurring earlier this year in Winnipeg.

“We have some folks who are actors but learning the language and some folks who are speakers who were learning the acting process as we went along,” said Cary Miller, a University of Manitoba Indigenous Studies scholar who served as the project manager.

In addition to her knowledge of the Ojibwe language, Miller was recruited to the project for her extensive knowledge of the film.

“You had a bunch of Star Wars geeks that came together,” Miller said.

Aandeg Muldrew, an Anishinabe educator whose middle name is Jedi, had never voice acted before he successfully auditioned to be the voice of Luke Skywalker.

“I think my journey mirrored Luke’s journey a little bit,” he said, adding that having such a major role was “a little bit daunting.”

Like the protagonist at the film’s outset, Muldrew wasn’t confident in the role assigned to him, but like Skywalker he gained confidence as the film progressed.

Not an Exact Translation

Miller said translating the script into Ojibwe was the first project’s first step, followed by adapting the Anishinaabemowin script to fit what appears on screen.

“That's where we take those phrases and try to match them with the amount of time that the actor is speaking in the film and their lip movements,” Miller explained.

This proved challenging, requiring the translation team to work long hours “sweating in that studio,” said Pat Ningewance Nadeau, Miller’s University of Manitoba Indigenous Studies colleague who worked on the film as a translator.

“If somebody's lips were closed, we had to come up with a word where you close your mouth when you're making that sound, so we had to change the script,” said Nadeau.

“But the result is that when Carrie Fisher is moving her mouth in the film, it really looks and sounds like she's speaking Anishinaabemowin,” she said, referring to the actor who played Princess Leia in the original films.

Having to synchronize his Anishinaabemowin lines with the English lip movements of his character wasn’t an issue for Dennis Chartrand, who did the voice for a famously masked Darth Vader.

In addition to playing Vader, whose iconic distorted voice was acted by James Earl Jones in the original, Chartrand assisted with some of the project’s translation work, assisting his fellow actors, some of whom aren’t fully fluent in Ojibwe, to ensure they pronounced all their lines correctly.

He credits the project’s director and voicing coach, Ellyn Stern Epcar, who also directed the film’s 2013 Navajo dub, with helping the actors “be in character and stay in character.”

Chartrand added that “a little bit of technology is going to bring this Darth Vader voice into Ojibwe very powerfully.”

“You're probably going to get goosebumps when you hear it, even though you might not understand,” said Chartrand, who comes from Pine Creek First Nation in northwestern Manitoba.

The norms of the Anishinaabemowin language required some lines to be modified, because a literal translation wouldn’t make sense.

In the original film, referring to Chewbacca, Han Solo’s tall, hairy copilot, Princess Leia says, “Can somebody tell this big walking carpet to get out of my way?”

In the Ojibwe cut, Leia, voiced by Theresa Eischen of Little Grand Rapids First Nation in eastern Manitoba, says a line that translates to, “Can somebody get this big, hairy thing out of my way?”

“Our language is very descriptive,” Eischen explained. “Even that line that I really love, that's not really what they're saying, but it still means the same thing.”

For May the force be with you, the film’s translators decided to use Gi-ga-miinigoowiz Mamaandaawiziwin, which situates the phrase within Ojibwe teachings, Chartrand explained.

“There's a whole lot more syllables, but yet there's no other thing that we can say with that one,” he said.

Ajuawak Kapashesit, who voices Han Solo, credited the translation team’s creativity.

“We're talking about concepts that are not your typical language class subject. We're talking about starships and space travel and lightsabers,” said Kapasheit, who was raised on the White Earth Reservation in Minnesota, located northeast of Fargo, North Dakota.

“One of the things I find really exciting about the Ojibwe language is it has a lot of these little pieces that you put together to make these words, so it's really flexible in that way.”

How Star Wars Is an Indigenous Story

The actors noted clear parallels between Star Wars’ narrative and the history of Indigenous Peoples on Turtle Island and beyond.

“Indigenous people around the world are the Rebel Alliance and the Empire is the colonial forces that try to take away our harmonious connection to everything around us — the land, the water, the animals — which is so precious to us,” said Chartrand.

Eischen noted the “resiliency” Leia shows after the Empire destroys Alderaan, her home planet, as well as the striking similarity Chewbacca has to the Sasquatch, a sacred being to West Coast First Nations, and how Yoda’s object-subject-verb speech patterns are reminiscent of many Indigenous languages.

“Luke Skywalker living in this rural area away from all the things he wants to do, it's kind of like living on the rez. Sometimes you're just kind of isolated in a lot of ways,” Kapashesit said of Tatooine, the protagonist’s home planet.

Han Solo’s Millennium Falcon ship similarly reminded Kapashesit of where he grew up.

“That's just him in his rez car — like it has its difficulties, there's things that are not working all the way they need to be, but he loves it, and he's going to make it work,” said Kapashesit. “That's very relatable to a lot of Indigenous people.”

There’s a reason the film resonates with so many different cultures, resulting in it having been translated into more than 50 languages.

“There's something just about the universality of this story,” Kapashesit said. “The characters involved, how there's this force around them that they're all fighting against, and in many times, it seems like the odds are stacked against them, but they all work together in order to make big change.

“That’s what a lot of Indigenous communities have come against and continue to fight through.”

Muldrew, Luke Skywalker’s voice, said in the future he hopes to see more than just Indigenous language translations of popular settler films.

“I'd just like to see more of our own stories being on screen — our voices and our faces as well,” he said.