Imagining a world without police

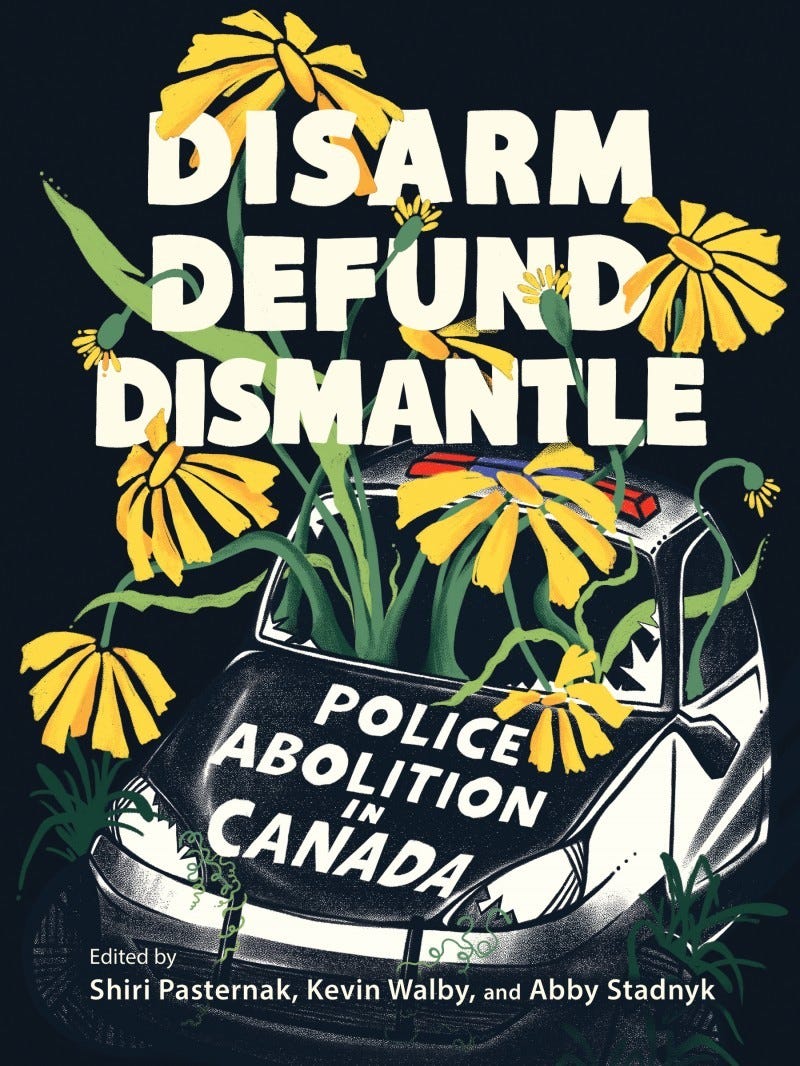

Q&A with an editor of Disarm, Defund, Dismantle: Police Abolition in Canada

There’s a tendency in some Canadian circles to suggest police brutality is mainly an issue in the United States, that Canadian police are more genteel and accountable, and that while the corruptions of the American carceral system are well-documented, the system in Canada essentially works.

A new collection of essays called Disarm, Defund, Dismantle: Police Abolition in Canada, published by Between the Lines, rejects this notion wholesale. It contends racism is inherent to policing wherever it occurs, and that we must begin to conceive of a world without it.

I spoke to one of the volume’s editors, Abby Stadnyk, about the racist roots of policing, particularly in Canada, the role of social work in upholding it, the inadequacy of police reform and what exactly a world without police looks like.

The interview has been edited for clarity and condensed for length.

How do you get involved in police abolition work?

It came about through my work with incarcerated people. About ten years ago, my focus was more on prison abolition. But as I've developed as an abolitionist, I've come to understand the interconnectedness of all of those aspects of the penal system, with police being an integral part of that. The collection attends to this nicely, I think, as well the intersection of social work as part of the carceral or the penal apparatus. I started off as someone who was working as a volunteer, teaching creative writing classes in jails and prisons in Saskatchewan and Alberta, which is something I still do.

I'm glad to know a lot of people inside, particularly Indigenous men, and glad to hear their critiques of the system. I don't think I would have called myself an abolitionist when I first entered into the system as a volunteer. I would have had a critical orientation towards the system, but I don't think I had imagined at that point what it would mean to completely do away with it. In particular, my friend Corey Cardinal, who passed away in June, was a Cree prisoner justice advocate. He did a lot of organizing inside with other prisoners for prisoner rights. He put forward some really strong critiques of the prison system as an arm of the colonial state's genocide of Indigenous Peoples. Through that relationship with Corey and other relationships with people inside, I got to see the very real harms of that system and then understand how policing is, of course, the front lines of the prison system, in terms of shuttling people into it, removing people from their families, from their communities and from their lands. That's particularly relevant, of course, for Indigenous people, who are removed from their own lands and then put into a foreign colonial system.

I find it really interesting that a lot of people would see social work as sort of a counterpoint to policing and incarceration, but you’re saying it’s part of it. Can you tell me a bit more about how the two professions are integrated?

There are two chapters in the book that deal with this. Many people talk about that school-to-prison pipeline, but there’s also a foster home-to-prison pipeline. There are ways in which social work as a practice and profession has historically — and presently — been complicit in removing children from their families and into sort of an institutional context. There's an institutionalization that continues in the prison process.

You often hear the idea that funds should be shifted away from police, perhaps to bring more social workers into the system of policing. And the arguments that these chapters in the book make is that we need to take a step back from that as a solution, because that just further entrenches social workers within the carceral network, and instead think about how to re-imagine social work as a practice of care that doesn't remove children from their families. I think there is work going on around that for sure. And these chapters do a good job of speaking to how certainly there's need for networks of care and being aware when children are in harm's way. But removing children from their families doesn't seem to be a solution that creates any sort of social cohesion for anyone.

In the introduction to the book, it says that the collection suggests that it is possible to imagine safety differently, it is possible to respond to distress and harm with care, and that in order to do so, police power must be eroded and dissolved. What does that look like to you?

Abolition is partly a future-oriented project. So how do we think outside of a system that we're so deeply entrenched in? I mean, this is a really hard question because police, prisons and that whole apparatus is so naturalized that most people in society generally take it as a given. Like, what would we ever do without police and prison? So in part, abolition just gets us to think about what we could do instead. But I think there are abolitionist practices that are ongoing. There are ways that communities are taking care of each other without the assistance of police or prisons, because police have never been there to protect certain groups of people in the first place. Historically, the police have never been there to protect Indigenous people. They've been part of the operation of disenfranchising Indigenous Peoples and removing them from their land, so Indigenous Peoples in general have always had to operate without police protection. The police generally protect property interests, corporate interests, etc.

Over the COVID period, we saw people come together in a lot of mutual aid projects to support each other, whether that be financially or through food or through other means of support — just people coming together to build community. We have this very atomized community, especially in a white settler context. We need to think about how we build those community connections through supporting each other again. I think that's abolition in practice, in a sense.

There’s a chapter in the book by Vicki Chartrand where she talks about grassroots justice and what she has learned from Indigenous communities in particular, who have had to deal with the crisis of Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women, Girls, and Two-spirit People about how, again, the police have not been there. If an Indigenous woman is reported missing, there's all of that deep racism that exists there, so communities have done that work themselves in terms of organizing searches, marches, vigils and all kinds of practices that people have engaged in to raise awareness, take care of each other, and try to find members of their community who are missing. Those are some examples that come to mind for me.

For me, abolition requires that we shift away from this kind of punitive mindset that the criminal legal system operates around, and that we shift more towards a restorative mindset or transformative mindset where we think about what do people need to support themselves and to live satisfying lives of abundance and joy where they're well supported, instead of this situation we find ourselves in now with hierarchy, capitalism and the punitive logic of the criminal legal system.

More liberal, mainstream types dismiss abolition outright and say we should just focus on reform, community policing and re-allocating police funds elsewhere. Why is that insufficient?

What I know most is in the Indigenous context, where there's been so many reforms that have been put in place to try and lessen the number of Indigenous people who are incarcerated. Those reforms aren't working.

My argument would be that those reforms aren't working because they're not actually intended to work. This is an abolitionist refrain, that the system isn't actually broken, it's working as it's intended to work and as it has always worked — to remove people from their lands, displace them, and to fragment and fracture communities and families. Reform is a distraction from what we really need to be looking at, which is imagining different modes of safety. A lot of the reforms proposed, like body-worn cameras, are just another way of increasing surveillance, so those sorts of things I think are problematic.

There's so much research that shows policing and prisons are systems of harm. They continuously harm certain populations and support others, and it's baked into those systems. It's how they were conceived and how they continue to operate, even though there may be some good people who get engaged in these systems because they want to make change.

I'm sure you're very familiar with this line of questioning, but people who dismiss abolition would say, well what about the worst, most heinous violent criminals, like Paul Bernardo? How does a society without police or prisons deal with these types of people? How do you rebut that?

That is always the question that people ask. It's sort of the most extreme end of what we're talking about. I’m convinced by a restorative justice approach that thinks about how to restore relations after harm has occurred.

A lot of what we see in restorative justice practices today is rooted in traditional Indigenous practices, justice traditions and legal orders that think about mending relationships and having healthy relationships at the foundation of our communities — the idea of relational accountability.

Restorative justice focuses on that restoration of relationships, whereas transformative justice takes a step back to think about how we create the conditions where certain harms don't exist in the first place. How do we create a world where people have housing, enough food, safety, etc.?

To ask the question about what do we do with the most heinous people takes us in the wrong direction. I feel like it's more powerful and has the potential for greater change if we think about how do we create a society that doesn't produce people who are serial killers? I don't know what goes into producing a serial killer, what sorts of conditions of violence and harm have to exist to create that outcome in the first place. So I don't know.

That's one approach to that question. But the other is to ask how many people in our prison system are people who have committed those sorts of heinous crimes? It's such a small percentage of people. Most people who are in prison are poor, are racialized, are people who are using drugs or some sort of substance for one reason or another, people who have violated their parole conditions, which often has to do with not being in a certain place at a certain time or using substances or associating with certain people.

The vast majority of people who are locked up are people who are oppressed in multiple ways, and then the system just oppresses them further.