Alberta's Health Care Bonanza

Dismantling Alberta Health Services creates a double whammy opportunity for privatization and pandemic complacency.

Securely re-elected in May, Alberta Premier Danielle Smith is now fulfilling her long-term ambition of smashing Alberta’s public health-care system into pieces.

What is being pitched as an effort to decentralize the massive one-size-fits-all Alberta Health Services (AHS) bureaucracy in fact does nothing of this sort. Instead, it breaks AHS into four faceless bureaucracies, each of which will be responsible for a facet of health care across the entire province.

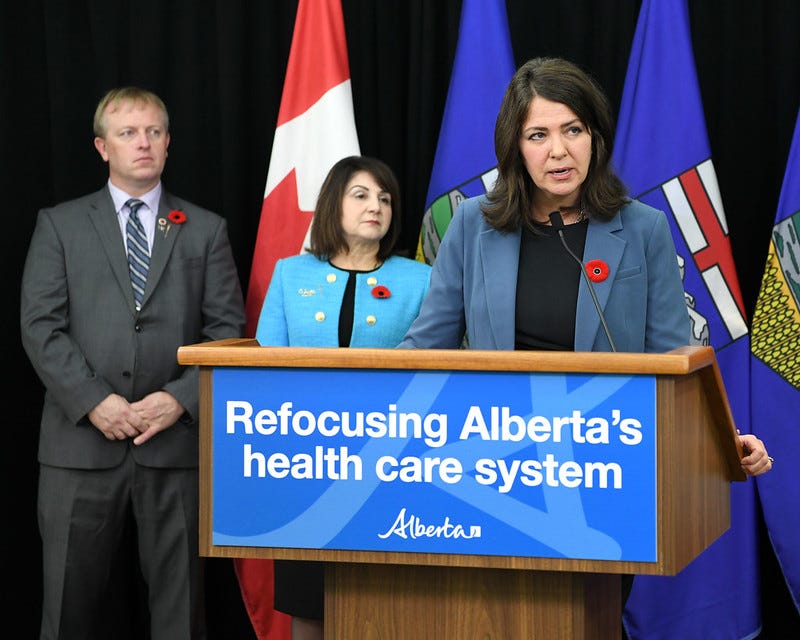

AHS will focus exclusively on acute care, and is likely to be renamed, while other sprawling health agencies will be created to cover primary care, continuing care, and mental health and addictions, Premier Smith and Minister of Health Adriana LaGrange announced on Nov. 8.

“Drawn and quartered was a medieval form of execution in which the victim was hanged, cut into four pieces, and the parts scattered,” wrote Globe and Mail health columnist André Picard, noting that Smith is bringing AHS “to the gallows.”

This process of “de-aggregation” is expected to take two years at a cost of $85 million, with the new continuing and mental health and addictions care agencies rolled out in spring 2024, and acute and primary care in fall 2024.

While AHS was nominally independent from government — much to the dismay of Smith and her clique of COVID denialists — the four new agencies will answer to a coterie of politicians and bureaucrats, rather than physicians and other health-care professionals.

“In a technical briefing, health officials were unable to point to another jurisdiction that uses the model proposed by the government, instead saying Alberta is a leader in health care,” CBC News reporter Janet French noted ominously.

Premier Smith insists that this isn’t a prelude to privatization, and that no jobs will be lost, but Alberta has long been a leader in health-care privatization.

Prior to 1994, Alberta had 200 local hospital and public health boards, each of which was able to respond to local needs. But in the neoliberal craze of the ‘90s, where cutting spending and taxes was the order of the day, Premier Ralph Klein consolidated these boards into 17 regional agencies, which coincided with a 17.6% cut to the overall health budget and 32% in cuts to hospital budgets in Edmonton and Calgary.

A decade later, Klein folded these 17 agencies into nine. And then in 2008, Premier Ed Stelmach consolidated the nine regional agencies into one agency to rule them all — AHS — which Health Minister Ron Liepert described as a “$13 billion corporation.”

Smith trotted out Stelmach, who chairs the board of the publicly funded Covenant Health system of Catholic hospitals, to endorse her plan to chop up AHS, alongside another washed up conservative — Dr. Lyle Oberg — who lost the 2006 Progressive Conservative leadership race to Stelmach and just so happens to be the CEO of private health-care provider MYND Life Science Inc.

Dr. Oberg will chair a new AHS board to determine the terms of its demise.

While it’s important to have a single unified health-care system that provides the same standards of care to people regardless of where they reside, with regional modifications in response to local needs, AHS was never intended to be that. It was always a cost-cutting measure, which naturally had the effect of reducing health-care capacity.

Nothing about Smith’s plans will change that reality. It will only make it worse.

Smith’s Nov. 8 announcement was preempted a day earlier by NDP leader Rachel Notley, who revealed a leaked copy of the UCP’s plans to not only dismantle AHS, but sell off public continuing care facilities.

Notley said that the documents were provided to her anonymously. I wouldn’t be at all surprised if it was sent to her by some UCP staffer to soften the blow of Smith’s announcement the following day.

"Is the premier actually committed to what’s outlined in these leaked documents?" Notley asked Smith in the Legislature on Nov. 7.

"One hundred per cent committed," Smith affirmed.

At the same time, Minister LaGrange insisted that “absolutely no plan to privatize health care” exists.

Indeed, privatization wasn’t mentioned at the Nov. 8 presser. But it didn’t need to be, because it’s already underway. Dismantling AHS simply makes privatization easier to achieve by breaking down the health-care system and selling it for parts.

“Blow it up and sell pieces off, that seems to be the strategy underway with this morning's announcement,” Friends of Medicare executive director Chris Gallaway said in a Nov. 8 news release.

It’s telling that continuing care and addictions and mental health are the first services to be decoupled from AHS.

Continuing care has already been largely privatized, which the NDP government did essentially squat to reverse during its tenure in power from 2015 to 2019. Out of 84 assisted living and long-term care facilities in AHS’s Edmonton Zone, for example, just 13 are operated by AHS, representing 15%, with the rest operated by for-profit corporations or charities.

According to a 2021 study from the Parkland Institute, the privatization of long-term care had fatal results during the pandemic, with private operators disproportionately short staffed, leading to workers coming into the workplace while sick so as not to burden their colleagues.

Meanwhile, the province’s so-called “recovery-oriented system of care” has been doling out cash to unregulated private recovery clinics like candy.

A publicly run facility, the McCullough Centre in Gunn, just west of Edmonton, was closed in February 2021 only for the government to announce a year later that it will reopen, with an operator to be contracted out after its renovation at public expense.

Dismantling AHS gives the government the opportunity to pull more of these types of stunts.

In Canada, primary care is already private in the sense that family doctors are small business owners, who bill the provincial government for their services.

The Canada Health Act, which enshrined Canada’s public health-care system as we know it, has nothing to do with health-care delivery, it’s all about funding for “medically necessary” health services, which inexplicably exclude dental care, medication and mental health services.

And while physicians aren’t allowed to charge for basic health-care services, that hasn’t stopped some from trying to do so, as evidenced by the recent case of Calgary’s Marda Loop clinic, which held off on plans to charge its patients four out of five days a week for quicker access to health care.

But this isn’t new. According to a 2022 study from Dalhousie University in Halifax, there are 83 publicly funded health clinics across Canada, including 14 in Alberta, in which patients are paying for expedited services — an apparent increase from the 71 clinics identified in a 2017 Globe and Mail investigation.

Don’t be surprised if the Marda Loop clinic uses the smokescreen created by AHS’s restructuring to resurrect its plans to offer basic health care out of pocket, a policy Smith endorsed as recently as 2021.

When Premier Smith resurrected former premier Jason Kenney’s “Public Health Care Guarantee” on the campaign trail, it meant that patients won’t have to pay out of pocket for health care, not that it will be delivered by a public provider.

But a consistent stream of government subsidies, rather than having to depend on patients’ paying out of pocket, would be a real bonanza for private health service companies. With steady government funding for basic health services, these companies can focus on pressuring patients to purchase premium services they don’t actually need.

On the acute care side of the equation, in February 2022, Kenney announced his ambition to increase the percentage of surgeries conducted in private facilities to 30% from 15%. A year later, that figure was at 20%.

An AHS that’s cut to the bone should have no problem reaching 30% and beyond.

Will contracting out these procedures reduce health-care costs? Not at all, considering these companies’ obligation to earn a return for their shareholders.

But never mind that, there’s money to be made.

We cannot lose sight of the pandemic angle of the AHS changes.

Smith has made no secret of the fact that were she in charge in the early days of COVID, she’d have done absolutely nothing, keeping the wheels of capitalism churning in full gear.

The Take Back Alberta fanatics who were instrumental in her political comeback list AHS reform as its major priority after pledges for there to be no more lockdowns or vaccine mandates.

Having a centralized health-care system broken down into four parts will make it much harder to do anything about COVID, if there were any political will to do so on any side of the elected political spectrum, which there isn’t.

How can one effectively coordinate the response to COVID infections, hospitalizations, the dangers of long COVID, the situation in long-term care or the mental health impact of living through a pandemic if they’re cordoned into four separate agencies?

In addition to precluding a coherent pandemic response, dismantling AHS will also make it harder to accurately determine COVID case numbers. CTV News obtained an internal AHS document that showed the number of Albertans hospitalized with COVID on Oct. 21 was 898 — nearly triple the 320 hospitalizations the government reported.

With AHS out of the picture, COVID numbers will be whatever the government says they are, if they decide to say what they are at all.

Even outside the context of a pandemic, University of Calgary public health law professor Loran Hardcastle writes in the Edmonton Journal, “with different areas of care now divided into four organizational silos, patients risk falling between the cracks rather than smoothly transitioning between, for example, acute care and continuing care or acute care and mental health services.”

No, AHS isn’t working. One need only look at the sheer body count of COVID in Alberta, or the fact that hospitals are having immense difficulty retaining staff, to reach that conclusion.

But Smith’s cure is worse than the disease. It’s hard to believe that isn’t by design.

Are we going to find Marshall Smith as chair of the new “Mental Health and a Addictions” agency?

What do you think?