Alberta recovery model gets mugged by reality

The latest drug poisoning statistics should give the recovery-oriented system of care's loudest proponents pause. But it won't.

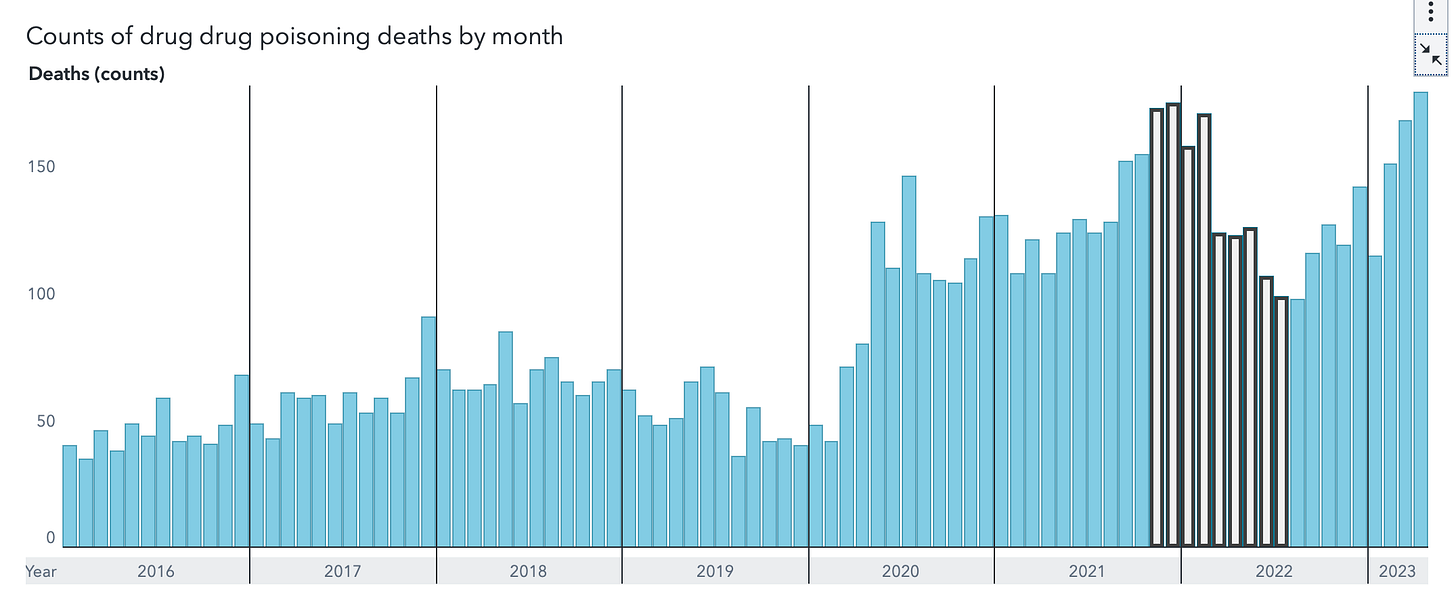

Alberta reached a grim milestone in April, with 179 drug poisoning deaths, the most on record, which we only learned last week. You have to go back to December 2021 to find the second-highest month on record, with 175 deaths.

The data for the first quarter of 2023 shows a clear upward trajectory, from 115 deaths in January to 151 in February and 168 in March, which indicates April’s record-breaking figure isn’t simply an unfortunate blip on the radar.

These sordid figures suggests the province’s recovery-obsessed approach to the crisis, for which evidence of its efficacy has been replaced with moral posturing, simply isn’t working.

But don’t expect its proponents, including Premier Danielle Smith, her chief of staff Marshall Smith and federal Conservative leader Pierre Poilievre, to admit fault.

Rather, you can expect the Smiths to use these deaths to bolster impending involuntary treatment legislation.

The recovery-oriented system of care doesn’t fail us, we fail it. So off to rehab you go, even if you have no intention of quitting drugs.

Poilievre, on the other hand, will likely just stop talking about it, like he did for crypto once prices collapsed, and move on to lying about something else.

Poilievre used less than a year of respite in drug poisoning deaths last year to argue that Alberta has “cut overdose deaths by almost half” by lavishing funds on private, under-regulated recovery clinics, contrasting this Alberta model with “woke” harm reduction policies.

Poilievre looks at a nine-month period — from November 2021 to July 2022 — to argue overdose declined sharply, ignoring that the July 2022 figure is still higher than at any point prior to the pandemic.

However, by Poilievre’s slippery logic, we can now attribute the Alberta model to an increase in overdoses, since he’s established a direct causal relationship between overdose figures and number of recovery beds announced.

In more intellectually rigorous corners, Calgary-based harm reduction activist Euan Thomson notes that at best the Alberta model has had no impact on overdose rates, which are still primarily the product of an increasingly toxic drug supply.

But the Alberta government has made decisions that exacerbated the situation, he wrote in his fantastic Drug Data Decoded newsletter.

Some of these were decisions of inaction — not introducing overdose prevention services into homeless shelters and not decriminalizing simple possession.

But others were active decisions to eliminate the province’s take-home hydromorphone program — the closest thing the province has to safe supply — and sending cops to downtown Edmonton and Calgary to arrest unhoused people for petty offences, including drug possession.

The latter point requires some elaboration. According to a brand new study in the American Journal of Public Health, drug busts lead to increased overdoses in the vicinity where those busts occurred, as people get increasingly desperate for their fix.

In a June 30 news release, Friends of Medicare executive director Chris Gallaway declared the Alberta model a failure, urging the government to adopt an evidence-based approach to the drug poisoning crisis.

“The situation in Alberta is bleak, and getting bleaker,” he said. “Six people dying from an overdose in this province every single day isn’t a success. This is an unmitigated crisis and we need the new Minister to start treating it like one.”

Gallaway noted that this crisis places strain on the broader, “already struggling” health-care system.

Alberta’s punditry has been uncharacteristically silent on the unprecedented spike of overdoses in Alberta, with the notable exception of Jason Markusoff at CBC News. Gary Mason, the Globe and Mail’s Vancouver-based national affairs columnist, also weighed in.

Radio silence from the Don Braid at the Calgary Herald, who lauded the UCP’s “revolution in addictions policy” in May 2021.

There were, however, two excellent pieces of reporting last week from Anna Junker at the Edmonton Journal and Joel Dryden at CBC News.

Dryden, shadowing two Calgary-based outreach workers, placed the spike in overdoses in the context of the increased circulation of “tranq dope” — opioids laced with tranquilizers, including animal tranquilizer xylazine.

The presence of xylazine is a particularly dangerous development. Those who use it can develop “rotting flesh,” which sometimes requires amputation.

“[I]t looks like their skin is, like, falling off of their body," Lauren Cameron, one of the outreach workers, said.

Making matters worse, xylazine counteracts the overdose reversal effects of naloxone.

Dr. Elaine Hyshka, the Canada Research Chair in health systems innovation at the University of Alberta School of Public Health, cautioned that it’s an “open question” which substances in particular are driving increased overdoses, because that data isn’t tracked.

"If we were taking this issue seriously, we would have public health officials out regularly, at least monthly, telling us what's circulating, what the impacts are on people, and how people can keep themselves safe,” she told the CBC.

While we don’t yet know what the overdose figures are for May and June, we do have weekly EMS response data for opioid-related events up to June 25, which tends to track closely with trends in drug poisoning deaths.

The most recent week for which data is available, from June 19 to 25, reached 275 responses — just one less than the record high from Nov. 29 to Dec. 4, 2021, suggesting the problem is only getting worse.

The increase in overdoses hasn’t been a secret for anyone working on the ground.

“It has been blatantly obvious from the number of responses done at agencies, by outreach teams,” harm reduction advocate Angie Staines told the Journal. “Just go stand Downtown, and look in every corner and you will see ambulances and fire trucks. I have never witnessed anything like it.”

She added that this underscores the need to give people who use drugs the “autonomy to make the choices that are right for them.”

If recovery is presented as the sole option, “we’re just going to keep burying people.”